Book.

The Oasis of Dreams

Chapter 4. Children of Distress

A. Without Motherly Embrace

Anyone who has grown up without a father and mother, without brothers and sisters, has seen conditions of distress. We are born into the world as premature beings, alone among the animals to require years of incubation. The parents’ home is the natural setting for this process; the warmth and care we receive there is vital to our growth. At the same time, we are naturally drawn to our mothers’ breast, eager for our fathers’ counsel. A mother’s kiss provides emotional fuel, while the father’s pat on the shoulder prods us forward in the race. For the most part, the students of Hadassim had arrived at the school without such things.

Orphans of the Holocaust, like Ephraim Gat, had burst through their childhood shells in unparalleled distress, alone and unsung. But in Hadassim they were greeted with gentleness by Rachel Shapirah, and nurtured through their adolescence at the hands of Yehudit Frumin and Shoshanna Lerner. Rachel and Jeremiah chose the kind of teachers and counselors who could fill the void left by these children’s losses, who could step into the shoes of their departed parents.

Avinoam Kaplan and Danni Dasa, both of them sabras, were there to offer praise and unfailing support; as was Sholomo Fogel – the field corps coordinator and hardened Palmach warrior – as were Michael Kashtan, Arie Mar, Shlomo Achituv and Zeev Alon. Rachel and Jeremiah asked these men to be fathers, not mere instructors. Thus was Hadassim not only a school but a home for the children of the Holocaust, and with clear goals and unsparing dedication Rachel and Jeremiah made our village into an unparalleled success.

They weren’t philosophers. They weren’t the sort of educators who preserved their insights in writing. Rather, the Jeremiahs were precisely the ideal men and women of action, who could apply their knowledge to demonstrate to the world how children who bore horrific scars could be lifted up, educated and set free to fulfill their original destinies.

Hadassim, as already mentioned, was also a home for Sabra kids whose families had either dissolved or else simply couldn’t provide for them. These children bore their own scars, which required their own tending. One of them was Avi Meiri, a son of one of Petach Tikva’s founding families. At the age of nine, after his father died in 1949, his mom had felt helpless to support her children and sent him away. Of the Sabra group to arrive in Hadassim, the child with the harshest background, by far, was Gideon Ariel -- the man behind this book.

While the predominant emotional state for the Holocaust orphans was one of deep shock, the principal emotional trauma for the Sabra kids stemmed from feelings of abandonment. Teachers and counselors were charged with pulling them together, bonding them so that they would know that not everyone was against them, that they had a home in Hadassim.

Hadassim was also a place for a number of highly gifted children, whose parents simply lacked the means to further their intellectual enrichment. Home was simply too stifling a place for them. I myself belonged to this group. Hadassim provided me with a sphere of action within which I could criticize the way of things, dispel myths and dream of alternatives. But just a s Hadassim was a good fit for this group, so too were we a good fit for Hadassim; we helped Rachel and Jeremiah realize the goals they had set for themselves.

Then there were the rich kids, born into privilege but sent to Hadassim in order to discipline themselves, to let go of their worldly goods and built up their hearts. One of them was Uzi Tzinder. His family owned a book-binding company, but their prosperous living didn’t stop Uzi from being held back a year in school and bullying his younger brother. His parents decided that he needed a place like Hadassim to put him on the right track, and they were right. Uzi and the other brats were literally rescued by Hadassim from their softening and corrupting backgrounds. Hadassim toughened them up. The staff had a hard time of it with them, to be sure; Micha Spira (Professor Moshe Schwabe’s grandson), for example, graduated from Hadassim only after a lengthy series of crises and disciplinary nightmares. Nevertheless, Micha was a central figure at the school, excelling with the dance troupe and thereby shaping the life that enabled Hadassim to become a leading Israeli institution.

The children that assembled in Hadassim, deserted and defiant, were therefore an improbable but dynamic mix. It would seem implausible that European orphans could engage in organic dialogue and form a creative community with Sabras and discipline cases, that all of these children together could eventually ascend to the nation’s social elite. Most of them had arrived there with heavy psychological barriers, unproductive of a healthy development. But Hadassim made it happen. Understanding the phenomenon of integration between children borne of the Holocaust and Israeli children borne of distress – understanding how their disparate psychological shadows were neutralized – will enable future educational systems to repeat this achievement. If we can alter the course of deterioration for other such children today, if we can even partly stem that tide, we will reverse the earthly diseases of tomorrow, the destructive scourges of poverty and war, each of which originate with distressed conditions and unfortunate childhood backgrounds.

The Hadassim model will fit this endeavor better than any alternative theory. The super- theories of education in our enlightened countries should be derived from this model.

B. A happy woman

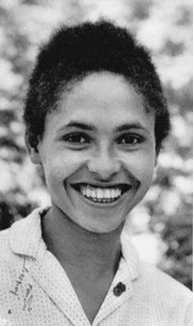

My first sight on my entry into Hadassim, in 1952, was a young black girl. The Ethiopian wave of immigration hadn’t yet begun, so the African workers who are now a common fixture in Israel weren’t familiar to our eyes then. Being black in those days was still something rare, even bad, in our minds. A black cat symbolized catastrophe; evil witches were always portrayed in deepest black.

Six years later, when I served in a paratrooper division, a group of soldiers from Uganda and Congo trained with us. One of them turned out to be Idi Amin. Our meeting with them was surreal: they might as well have been from outer space, as far as we were concerned. Aside from the few African ambassadors serving Israel, blacks were still only seen in films. And yet, here she was in front of me, a black girl in Hadassim. I had to rub my eyes to check that I wasn’t dreaming. Her name was Miriam Sidranski-Katzenstein; she was one year below me, in unit B, and apparently well adjusted and accepted socially.

Miriam Sidranski-Katzenstein

I was part of unit C, with Danni Dasa. Without him as our instructor, Hadassim would have been an entirely different institution. The same evening I arrived, Danni gathered everyone into the club and said, “Rising time tomorrow is at 6:00. At 6:30 you’re to present yourselves on the kurkar [a trail of limestone] in front of the dining-hall for running competitions.”

As with most kids, I had my own macho dreams of becoming an athlete, though I never gave it sufficient effort. I always considered sports as a means and not an end. For me, the ultimate arena was the swordplay of ideas, the eternal dialogic back-and-forth between the gods Moses and Demosthenes, in a comp etition for truth. But I loved running matches insofar as they stimulated my own intellectual fire. I readily adopted the Greek maxim: “A healthy mind in a healthy body.”

That night I went to sleep with a happy heart, hoping that Danni could turn me into an athlete. Chilli asked me how fast I’d been able to go so far.

“Worse than the worst,” I answered.

Chilli encouraged me: “Well, you just sit on my shoulders, then. We’ll come in first together!”

Everyone laughed because I was big and Chilli small, and then we all fell asleep.

I was the first at the kurkar the next morning. (I’m always punctual.) The black girl stood next to me. Everyone had presented themselves by 6:40, and then matches were held between the boys of units B., C. and D., ages eleven to thirteen. Chilli came first in the boys’ group, and the black girl took first in the girls’. What was surprising was that she also managed to place third in the joint boys-girls race.

“Who’s that black girl??” I asked Gideon Ariel, in envious disbelief. “Don’t ask!” he answered. “She’s the Hadassim Queen.”

Naturally, as I followed everyone to the dining hall for breakfast, my thoughts went immediately to the biblical Queen of Sheba.

Miriam eventually joined Israel’s national sprint team – when she was in the eleventh grade. She broke Israeli records in the one-hundred and two-hundred meter runs, and went on to represent Israel in the Tokyo Olympics along with Gideon Ariel.

Miriam was born in 1941, in the Belgian Congo, to Luisa and Yechiel Sidransky, an African mother and a Polish father. Yechiel had studied medicine in Belgium, so he was spared the agonies of Auschwitz as a government doctor in Congo during WWII. Miriam’s mother had died in a car accident shortly after her birth, and until 1946 she was raised by Congolese nannies while Yechiel saw to his patients day and night. In 1946, about half a year after WWII ended, her father returned to Belgium. In the meantime, she was sent to live in a convent, where she spent the next four years under a strict Catholic educational regime.

In 1949, however, one of Yechiel’s friends came to visit from his Polish schtetle, and he was shocked that a Jewish girl should live in a convent. He persuaded Yechiel to send her to the summer camp in Hadassim, then dire cted by Walter Frankel, the Jerusalemite agriculture teacher. The kids were mostly well off, sent there by their parents to experience a summer in paradise. Within a few years, Jeremiah had succeeded in attaching to Hadassim a reputation as an inland Garden of Eden.

Miriam: “I spent July and August of 1950 in Hadassim, and after that I told father that I was going to stay there. I decided that my place isn’t in some dark European convent, but in the shade of Israel trees. He went back to his Belgian projects, and later moved back to the Congo. Hadassim became my true home.

Miriam continued to live in Hadassim through her graduation, even through her studies at the Wingate Institute (Israel's National Center for Physical Education and Sport). She refused to live with her father, because her dialogic existence in Hadassim had lifted her above the mainstream patriarchal values, above her contemporary civilization.

“There was a cultural gap between my father and me. He hadn’t raised me or educated me; I was an independent spirit, and here, suddenly, he wanted to tether me to his own ways of life.”

There was no vestige of discrimination in Hadassim; Rachel and Jeremiah had purged their community of the racism in the culture. Hence, Danni Dasa was able to identify and cultivate Miriam’s unique attributes. Miriam: “ My skin color was treated as insignificant.” At the same time, fate had assigned to her the wonderful dance coach, Greta Sa lus. “When she first saw me in class, Greta came up to me and told me that I was a beautiful woman, that I moved beautifully, and she suggested to me that I should

take up dancing as an antidote to the masculinity of sports.” Greta guided Miriam with motherly intuition an helped her locate her feminine identity, something she had lost touch with in her infancy, when her mother was taken from her. The two of them, teacher and student, formed the mother-daughter intimacy that Miriam had always craved.

Years later, I would eventually meet Dr. Yechiel Sidransky during his temporary stay as a family doctor in my residence. I asked him what had originally moved him to send Miriam to Hadassim.

“My work in the Congo was my life’s mission. I didn’t have time even to learn to care for her…Hadassim seemed a convenient arrangement, and I suppose it turned out an ideal setting for her. The result speaks for itself.”

In 2005, we met with Miriam and her husband in their home in Kfar Shmaryahu. We sat together on their balcony and drank orange juice. The grass that filled the outlines of their estate was pristine green, and the trees blossoming. Today, she works in physical education for the elderly – and it’s safe to say that we don’t often meet anyone as irresistibly happy as this woman. “Hadassim meant the world for me. I’d never felt so good, never been received with such open arms. I was really loved there. And what is life without love? That especially was what shaped my personality and helped me as an athlete. I’m a happy woman today, only by grace of that magical first home.”

C. From The San Diego Orphanage to Municipal Corporations’ Development

Hillel Grudzinsky-Granot, nicknamed ‘Chilli’ in Hadassim, is easily one of the great optimists in the whole land of Israel. He sees the positive in every aspect of every issue, and the same goes for his appraisal of Hadassim. It is men like Chilli who always keep in mind the ideal Israel -- Israel as it was meant to be – during moments of national crisis. But if the profession of psychology and the wisdom of conventional educators are to be trusted, his early childhood in South America should have made him a pessimist – an angry, frustrated and hostile human being, rather than the ebullient man we know, a man whose joie de vivre is manifestly contagious.

Hillel Grudzinsky-Granot

Chilli was born in Buenos Aires in 1939, the second son of Yael and Meir. His parents had emigrated from Bialystok, Poland, in 1938, and settled in Argentina with their daughter, Hanna. Of course, it turned out that they’d left the frailest country of Europe on the very eve of WWII, leaving behind the death and destruction that would easily have befallen them. That fact alone constitutes the deepest source of Chilli’s optimism, who senses that events have been guided for him by an angel from on high.

He was a one year old child when his family picked up and moved again, this time across the Chilean border, where his father opened a furniture store in San Diego. Two years later his father was dead, leaving the mother and children, an eight year old daughter and three year old son, alone in a new country and a still unfamiliar language. Though Yael continued to run the store, Chilli was sent to a Jewish orphanage. His most intense memory of Chile is still the spontaneous and heart- lifting jubilation of Chilean Jews on the day the UN General Assembly voted to ratify Jewish statehood in Eretz Israel. That event, incidentally, is the kind of moment that anyone from the time will remember; they remember it the same way Americans of tomorrow will begin asking, “Where were you on the morning of 9/11…?”

In 1950, Yael Grudzinsky decided to immigrate to Israel. She had sent the children, now ten and sixteen, ahead of her to their new home, until she could sell the shop. Hanna and Chilli would spend over a month at sea, transferring to another boat midway to their new homes. Their aunt sent the boy to Hadassim within three days of his arrival, while the older sister went to the Ayanot Youth Village.

Chilli: “I was ten years old when I settled in Hadassim. I only spoke Spanish, so I couldn’t communicate with anybody. I didn’t understand a word of what people were saying to me. But there were two languages I learned immediately: fighting, and marbles. They called me ‘Chilli’ because of the way I held the marbles and because of where I’d come from, and the name stuck. There were many kids there from Romania, Poland, and the Arab countries, so everyone but me could at least talk amongst their groups if they didn’t have any Hebrew. What the hell was I going to do? I was a short, sheepish, chubby, freckled – all the ingredients of a sorry childhood. And I was terribly homesick; all my relatives in the country were too busy for a visit.

“It was Rachel and Jeremiah Shapirah who rescued me from this, giving me the personal and familial attention I needed. Rachel asked Yehudit Zeiri to give me Hebrew lessons, even though she didn’t have a word of Spanish. Happily, I found I could start chatting with the other kids in a matter of weeks.

“The way I see it, the miracle of Hadassim consisted in a community of both wisdom and cultivated friendship. My very first Friday in the village, the children were all gathered on the fields, the boys in their white shirts and khaki pants, the girls in blue skirts. Those uniforms helped stress the ideal of social equality: no distinctions between rich and poor, masters and servants. Everyone danced in one collective formation, as Danny [Dasa] instructed, and though I didn’t speak their language I could still join hands in the circle. That kind of Folk-dancing was the first Israeli language I came to understand; it was a unifying language for all of us.

“Our social counselor was Avinoam Kaplan. He’d been a commander in the Hagana before the state was declared, and he continued on as an officer in the IDF. And he was also a natural science teacher in the village, a capacity that enabled him to spread in us the love of the land. He embodied, for Sabras and foreigners alike, the genuine Israeli.

“My mother immigrated after a year. I was so excited at the prospect of seeing her that I was speechless for two days, but then she told me she wanted me to leave the school. I refused. I’d fallen in love with the Israeli spirit in Hadassim; I’d finally come into my own, I was good at sports – I was really part of something there. Danni Dasa had built up my self-esteem as an athlete, and it wasn’t long before I’d lost weight and made good friends like Gideon Ariel. In time I’d become active as a labor coordinator, a member of the student committee and its representative in the student council. I’d begun tutoring younger kids in the eleventh grade, which helped finance my studies independently. All of these roles helped solidify my identity with others; Hadassim was an irreplaceable experience in this regard, bonding me with my fellow Israelis to the end of time. And just as it made me an Israeli, it was also where I met my wife, Talma.

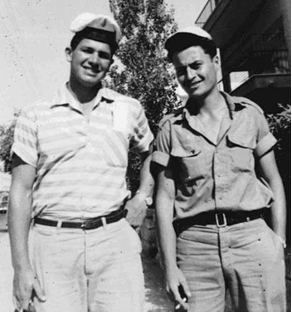

Gideon and Hillel

“When I joined the IDF I became a major, and then a senior officer. When I was done with the army I headed human resources for the cities of Kiriat-Gat and Petach Tikva, where I helped economic development by involving urban corporations in the public sector. Local companies, of course, are the financial level the government needs to manage life for its residents and further social goals. That type of thinking was only possible for me because of Hadassim. ”

Nurit Gantz was Chilli’s girlfriend at the school. She tells us that he was “popular, a great dancer and a capable social leader. It’s a pity that he didn’t go into politics. He could have raised the bar for Israeli politicians.”

Chilli: “Nurit was a real beauty. We were together only briefly, spending time at the movies or sitting in the quiet on the garden bench. That’s what dating consisted of in those days. Two months went by and I was asked to replace one of the counselors in our unit, so it was part of my job to start off the communal meals with “Bon Appétit.” And that led to an incident. One day at the dinner table, as I opened my mouth to commence the meal, Nurit interrupted me and started giggling. I asked her to stop, but she just kept laughing. So I stopped talking to her. She sent me a letter, asking me what was wrong, why the silence. Anyway, I explained why, and that was that…”

Nurit Gantz and Moshe Frumin

“Chilli and I have been friends for 56 years,” says Gideon. “As far as I’m concerned, he represents more than anyone the magic of Hadassim: an orphan in a strange land, surrounded by strange customs and a stranger language, became the center of our social life – so much so that Hadassim would be nothing like it was without him. I even doubt that it would have reached the academic heights the way it did if it weren’t for him. Had he gone to another school, without the principle of dialogue and creativity, without the dynamic social engine of Hadassim, his social gifts would have gone undiscovered and undeveloped. At the same time, whoever owed his personality to Hadassim owes at least part of that to Chilli!”

Chilli has always been a friend to everyone. The three of us, Chilli, Gideon and I, recently went to visit Maghar in the Upper Galilee, to discuss the Hadassim model with the educational directors there. Chilli immediately established a rapport with the three Druze brot hers who represented the village, members of the Dagsh family. In addition to educational matters, he offered to help solve their budgetary problems. It was obvious, from his entire attitude, that he did it out of comradeship; his whole presence made it easy to talk and share ideas openly, and it wasn’t long before we started planning for a Hadassim-type school for the Druze, Christians and Muslims in the village.

D. “I thought, how come successful people graduated from Hadassim”

Abraham Korkidi, Rosa and their three children enjoyed a happy, prosperous existence in the city of Bergama, Turkey. Abraham had his fingers in various businesses in town, and there came a day when one of his workers told him that the authorities were planning a pogrom for the next day. He wasted no time dragging his entire family to Eretz Israel, relieved but penniless. Back home, the worker’s advice had proven sound, and meanwhile the Turks took little time disposing of Abraham’s erstwhile possessions.

Despite their sudden break with their lives in Turkey, the family continued to flourish in Eretz Israel; Abraham was successful in his new business, and was soon blessed with three more children. The youngest, Esther, would become a good friend of ours. She was the same girl we were so smitten by in the Filtz Café on the Tel Aviv shore, on the morning of the Normandy landing.

Esther: “I lived my first years under the shadow of my mother’s terrible illness – breast cancer. She was always in bed, in constant agony, so the atmosphere at home was one of burden and anxiety. I learned to read at a very young age, and from the age of four I would wile away the hours reading romance novels. That was probably why it seemed a natural thing to me when Rafi Shauli1, one of the neighbor kids (and a year older than me), used to tempt me into the restroom, where he would undress and coax me into playing sexual games with him. Unfortunately, that was something that made it hard for me to get close to boys when I was older.

“My father used to take me along to the Filtz Café on Fridays and show me off to his friends, flaunting my beauty. That was where I met Gideon Ariel, Asher Barnea and Uri Milstein for the first time. I liked Gideon: He was handsome, in his own quiet way, and he radiated a kind of inner strength. Uri asked if I’d heard about the Normandy landing, and I answered that it didn’t interest me. Uri scowled in contempt. I told him, pointedly, that he was being a little conceited…

“I saw Gideon again a few days later, and he invited me over to his house. I was hoping that he had something in mind for us similar to what Rafi Shauli was so fond of doing, but what Gideon really wanted was to show me a secret door in the wall and what was behind it: guns. He told me, very proudly, that his father ‘kills the British.’ I ran home straight away and never said anything to anyone about it -- not until today.

“My sixth birthday came and went without any celebration, as mother’s situation was really terrible. She was finally taken to the hospital a few days later, where she died within days. I was kept in the dark about this, told that she was alive and awaiting recovery in the hospital. They told me that for the next nine years.

“I was sent to a boarding school in Naharia as soon as mother was out of the house. I spent three years there, and they were good to me. The director of the school, Gershon Dahas, was extremely friendly. More significantly, though, he was active in helping refugees safely off their boats and away from prying British eyes. The whole school was part of the general operation, doing everything possible to stump the occupation authorities.

“Meanwhile, father had remarried, and his second wife ended up controlling most of her property. I absolutely despised this woman. He brought me back home when I was nine, and my step-mother had me live in the utility room next to the garbage. Father had become sick, too; he spent his last two years in bed, weak with heart problems. I was eleven when he passed away, at the age of forty. I was sent to Hadassim.

My stay in Hadassim was certainly an interesting period of my life, though by no means a perfect one. I couldn’t dance, I was bad at sports; I didn’t have a boyfriend. I was incredibly lonely, and horribly jealous of all the girls strolling back from the orange groves with hickeys on their necks. So I found refuge in books. ”

That’s what Esther told us; yet she continued to reflect, in almost the same breath:

“I always asked myself why Hadassim had bred so many successful people. I was the youngest of five siblings; my parents had died young from severe illnesses, which made for a difficult environment for a child, to say the least. My brother and I were fortunate to be sent to live in boarding schools – the others suffered more than us. Hadassim was huge benefit to me, in that respect: the secret of its success for children like me – the reason we were able to persevere and become successful -- was the solidarity it provided for us in those difficult times.

“I never went home on vacations. I always joined my friends, as all of us felt so comfortable with each other. They were the true family and support that we lacked from our parents and homes. It was a safe and easy atmosphere.”

The Hadassim experience gave Esther Korkidi the power to overcome her fate. There she was free to roam the expansive library, using knowledge to build up her self-worth. And that led her straight to her university studies in English Literature, where she continued to excel. Learning the value of labor in Hadassim was therefore an indispensable stepping-stone to her successful thirty year career as director of the export- import division of Gideon Oberson’s company.

But the fundamental ingredient of her upbringing in Hadassim was: Love. The dialogic connection between teachers and students she found there would ultimately lead her to Shiatsu therapy, where she could fulfill her yearning for attachment to the world.

Esther had arrived in Hadassim with a negative self-worth and sense of life, as well as a negative predisposition to the world in general. Negative energies tend to obstruct positive action. So while Hadassim gave her necessary social support, it didn’t immediately cure some of the dark spots she’d accumulated in her early childhood. It would take her another forty years before she discovered her calling in Shiatsu. On the other hand, it’s doubtful whether she would have gotten there at all without Hadassim.

Esther: “The toughest woman in Hadassim, Fili Alon – almost everyone was intimidated by her – showed me love; she said I was an ugly duckling, that I would turn out to be a beautiful woman someday. I was assigned to her work station, where I found a means of escape in manual labor. That experience later helped me see that my hands were my connection with the world.

When we interviewed her in her cozy and picturesque apartment in Jaffa, we found not only a workstation with an office but also a partner for conversation, someone who was willing to open up and answer any question, and even ask her own. We found someone who smiled intelligently but not cynically; someone who could even take a bad joke. As we parted, it struck Gideon and me that, while we may have missed her all this time, she hadn’t missed us. Hadassim’s contribution to her life was to help her discover herself.

E. Theorizing from Situations

Asher Barnea and Gila

I had five close friends in Hadassim: Asher Barnea, the freckled boy who arrived at the village in the sixth grade, the same time as me, in 1952; Gideon Lavi, who arrived a year later and was a year ahead of us; Daphna Urdang-Hadanni, a classmate whose intimate friendship with me was transformed to hostility after I ended our relationship after graduation; Arie Mar, our social instructor in the ninth grade, who along with Gideon Lavi helped implement my Lamed Hei project; and Michael Kashtan, my literature teacher (and another contributor to my project) with whom I kept in close contact until his death.

Gideon Lavi wasn’t terribly athletic, but he was certainly one of the wittiest and sharpest men I’ve known all my life. His witty repartee was a symptom of the Homo Ludens2: a high intelligence mixed with joy de vivre and playfulness – a high-powered spontaneity. These combined in him with attributes of the Homo Criticus: a probing, satirizing cultural depth. He probed and diagnosed the fallacies of his age, and he had the courage to point them out above the objections of others. He cared not a wit what other students had to say about him, because he found they had nothing meaningful to say. People like Gideon Lavi are rare in our world; in Hadassim, he was one of a kind. The moniker “Philphel,” meaning both “Pepper” and “Philosopher,” stuck to him there. He was the top Chemistry student in Arie Mar’s class, and this was a teacher who ran roughshod over his students with his harsh grading policies – the class average was 3.8 (on a scale of 10). Such notoriously low grades reflected his attitude toward grades as such as much as his estimate of his students’ mental acuity. The professor was even more cynical than Gideon. Nevertheless, the boy always managed to score a 10, so by junior year he’d already skipped ahead to the advanced senior level course.

Gideon: “Arie Mar was detached and cynical -- yet we admired him for it. We’d never met someone so etched with irony. Most of the other teachers were properly serious men; Shalom Dotan, especially, had a kind of exaggerated austerity. That could be why he lived so long, whereas Arie Mar died very young. Even Jeremiah, for his part, was so serious that he considered it beneath him to smile. Into this mix came Arie Mar, a totally foreign element. He came off as American; he was light, almost complacent; he was a world apart from the other adults.

“ Whenever a student called someone a ‘Shmok’ [Yiddish for “penis”], Arie would chide him: ‘If you don’t want something in your mouth, keep it out of someone else’s.’ He carried himself like he didn’t have a care in the world, like some American movie star. He completely won us over with his biting sarcasm. He’d sit there in the middle of class, his right leg crossed over his left knee, almost carelessly. It was inevitable, then, that he wasn’t terribly liked by his colleagues, and that he would experience tension with the directors.

“ He was a man after our own hearts. After mine, at least.”

Arie Mar

Arie Mar lived in the corner of unit E, at the end of the corridor.

He, Gideon Lavi and I made our own little triangle, a circle of philosophical discussants, to reflect and theorize from our own situations. The three of us engaged in dialogue on the model of the Homo Ludens-Criticus. We’d sit for hours with him in his kitchen, sharing biscuits and coffee, surrounded by steam from Chava’s [Mar’s wife] rare cabbage soup that Mar loved so much. And we shared something else -- there was no distinction of age or wisdom between us, not during these moments. No aspect of any issue was left unexplored, whether educational method, the Arab-Jewish conflict, the spreading corruption, the role of mathematics in human knowledge, Quantum theory ( including Schrödinger’s Cat), or anything else. Prominent in our discussions was the topic of the Israeli state and its structural flaws, a subject not commonly delved into in the 50’s. It was the era of myth, when most Israelis still believed that we were living in Utopia.

These conversations would frequently stretch long into the night, and they eventually stimulated my high point at Hadassim – my reconstruction and dramatization of the Lamed Hei episode.

Sometimes Shoshanna Lerner, our counselor, used to join and listen in to our dialogues in Mar’s apartment, and her keen observation during those moments still impress me today. Even today, in 2006, she remembers the Lamed Hei performance with such crystal clarity, and such palpable interest, that she nearly convinced me my own memory of it was imaginary. She brought it back to me, alive, because of her rare capacity for love.

Yitzhak, Shoshanna’s husband, had fought the Nazis in the Polish forests as a member of the resistance. Shoshanna would often retell his brave stories to us as our mouths hung open in rapture. It became clear to me then that the real Jewish heroes had fought in the European wilderness in WWII, not in the Katamon neighborhood of Jerusalem in 1948. And then the question occurred to me: why should Yitzhak Lerner be a lowly storekeeper in Hadassim, while Yitzhak Rabin, the man who slept while the Katamon battle was fought, was an IDF Brigadier General and head of the training division? After thinking over it for a minute, I raised the conjecture that Israel has built a mythological culture, one that would someday collapse. Arie looked at me for a second before his lips curled into an amused smile, and he said, “The solution, I suppose, is to leave the country – so long as it’s still possible.”

This time I didn’t know whether he was being serious, or just his usual ironical self. For me, emigration was never an option.

F. “Crazy men can also cry”

Daphna was always interested in joining our philosophical circle. We never allowed it, as her over-sensitivity was something of a burden to us. At the time I was determined to break up with her, as our relationship was becoming an anxiety-inducing wreck. Unfortunately I waited until I was leaving Hadassim to follow through with it, when she came for a last visit in Tel Aviv. It was a painful moment for her. Luckily, Arie took a liking to her, and Gideon even stepped into the boyfriend role for a short while. But the final decision as to whether she would join our discussions was mine, and it was a resounding “No.” I take it this contributed to the grudge that she bore me until the day she died. Today it strikes me that I made a terrible mistake. She had a deep and complex personality, and dialoguing with her would probably have ingrained something valuable in all of us.

Daphna was a very talented girl, after all. Her imagination was rich and her capacity for abstraction plentiful, though she lacked the biting wit and peculiar shrewdness that seemed a badge of honor in our group. On the contrary, Daphna could be quite vulnerable. She was easily hurt over innocuous things, and it was burdensome to keep reassuring her and revitalize our friendships with every little spat.

Daphna believed in the conflict model of friendship: emotional proximity resulting from emotional crises. Sometimes we’d just laugh it off, but we could also be rather impatient and angry. She was in the habit of reciting her own poetry, and took to complaining that her mother liked her sister better (she called herself the “ugly” one) -- none of which we took very seriously. She seemed childish to us. In retrospect, her oversensitivity was an expression of a truly poetic soul, perhaps her only real means of survival. Metuka remembers her as a brilliant writer, who simply lacked the warrior-spirit we valued in those days. After all, Heraclitus had taught us that war was the mother of all things.

So Daphna went running to cry on her friends’ shoulders, and they, in turn, declared social war on our little group. Tamar-Heibish-Keshet still harbors hostility toward me because of Daphna, after all these years. Metuka still reminds me of how I once tore an excellent piece of hers to shreds, bringing her to tears right in the middle of class. It looks like we marked her for life with our teasing; she went so far as to condition her attendance at one of our friends’ parties on my exclusion from the event. (Apparently, her son, Ran, still rails against me on internet forums.) Before she died, I wanted to ask her forgiveness for the way I ended our relationship. And so I ask, here and now, that the quanta will transmit my apology to her through my readers’ minds.

Tamar Heibish-Keshet lectured me on the phone, in 2005: “You misbehaved toward Daphna. The two of you were intimate, and yet you insulted her. You talked down to her. But this was a gifted woman, a wounded soul. She endured through some horrible things in life – her father fell in the War of Independence, and her mother couldn’t deal with her, so she sent her away to Hadassim.”

Daphna Urdang-Hadanni

“Daphna and I were indeed good friends in Hadassim,” I responded, “We had a great time together, much of it even stimulating. She wanted to pursue the relationship beyond Hadassim, but it was simply out of the question. It was the 50’s: no internet, no Skype, not even a telephone, so I didn’t think we could really maintain anything serious while we were apart. She couldn’t come to grips with my position, and the separation was hard on her.”

I gathered from Tamar’s reaction over the phone that she wasn’t too satisfied with my explanation. From her and Daphna’s point of view – perhaps it’s just a general feminine point of view – the answer was more likely that I had enjoyed Daphna’s company, but not for her own sake, not for the sake of understanding her. In their eyes it was never a friendship on my part, only selfish exploitation. To them, when I say that she was angry at me because I broke it off with her, even that constitutes an exploitative, egoistic interpretation.

Chava Mar was a nurse in the village clinic, and she was often there with us during our conversation. One evening, as she was serving us tea and cookies, she revealed the location of an extra key to the sickroom. Our ears perked up at this nugget of information, and we soon began using the “secret” room to hang out with our girlfriends – separately, of course. God knows it was more expedient than a heap of straw…

One Friday night, I remember vividly, Daphna and I left the dance hall (where both of us had sat awkwardly; neither of us was too eager to dance) and snuck into the sickroom in the clinic.

“If you look for the light in my eyes, I’ll be able to see the light in yours. That’s what the theory of Dialogue means, after all,” I said to her.

She answered: “I love you so very much, with the same intensity as a small child tastes the sugar on his baby tongue. Hold me tight, Uri…you are everything to me, and I’m everything to you…let’s come together as one.”

“But salvation only comes through war. War is the only thing that can truly connect ‘others’ [people who differ from one another].

"But I interview your exclusive future, or I am only accompanying it with a counterpoint3 or an echo. Sir Richard Burton, the great explorer of the Nile, of women's nakedness and the rain, was the true anthropologist of forgetfulness, of everything which others call 'living': they lived in the past while he created the blue bird in a more miraculous race than dream. Therefore he said that his best poetry was the one not written – like the blindness of the singer in the heart of his throat. I am trying to write my best poetry with you. Therefore I will probably never write it.

“Who is Sir Richard Burton?” he asked.

“What does it matter?! He’s just a metaphor I created for you. He also happened to translate A Thousand and One Nights from the Arabic and the Kama Sutra from the Sanskrit. My mother adores him, so I discovered his book in our library. He was a man of both the pen and the sword – a genius – who fought in the Crimea and in India, explored Africa and discovered the source of the Nile. He was the only non-Muslim white man ever to penetrate into the forbidden city of Mecca, disguised as a dervish…”

I wondered at that moment whether I could ever dare to do what Burton had done; I reflected on the Lamed Hei, on the “Hadassah” convoy where Daphna’s father was killed. Danni Dasa had tried to rescue him by aiming his sub-machine-gun at the ambush all the way from Mount Scopus. In contrast, the assortment of Palmach men who arrived in Jerusalem the same day did nothing to help. Who was the ultimate Israeli, I asked myself: Shlomo Fogel, the veteran of the Palmach worshipped in all of Israel – or Danni Dasa, a member of the Jerusalem “Etzioni” brigade so widely reviled? And I knew that it would be my gift to the village, on Independence Day, to reveal what I’d learned about Israel’s true heroes. Everyone would soon know our secret – Arie Mar, Daphna and my secret.

But this was our night. The Thousand and Second Night.

We snuck into the clinic, quietly, like two conspirators. There was always the fear that we could be discovered. Then we locked the door behind us and opened the window shutters, letting the citrus-scent and full bloom of flowers fill the room with intoxicating verve. Unfortunately, I wasn’t aware of my allergies at that point – the pollen nearly made me faint within seconds, and I felt a quick jerk in the chest, like my heart was crawling up my throat.

I sat there on the bed, and I could only think to say, “Forgive me, there are no short cuts.” “I’m in love with your for your intellect, Uri. I love you for the searching animal within you, your willingness to give anything up for everything important.”

We sat together quietly for a while, and then I began to recite one of my Aunt Rachel’s poems:

Looking upwards from below… Thus

With the sad and surrendering gaze

Of a slave, an intelligent dog. The moment is full and pure.

Silence

And a hidden longing

To kiss the master’s hand.

“It’s an accurate description of intercourse,” she said. “Do you feel like trying?” I searched her for an answer.

She didn’t respond. She felt a desperate need, in that moment, to whisper one of her own poems. I wanted badly to make love, though somehow she excited my mind more than my body. She was a mystery to me. I was still in the process of discovering women then, and here was a woman who loved me but wouldn’t reciprocate physically. It was an inert kind of love, almost indifferent. That’s when it occurred to me that surrender was a necessary condition for love. She would surrender intellectually, spiritually – but not physically. Those triadic elements are necessary for true love, at least for me.

Today I think I understand why her body didn’t surrender to me: she experienced love as a need, a desperate need that she projected onto me, not as an unbearable and irresistible joy. I was a means for her, not an end. But it all felt quite different then, when I was young. She might not have been sexy, but she was still a woman who loved me in her own way, and that was attractive. So as she kept reciting her short lines, seemingly oblivious to me, I moved closer. The poem was a lament about her love-hate relationship with her mother and sister. The lines revealed that she felt rejected by her family, that her sister got all the affection, that her mother, an art collector and gallery owner, was disgusted by her over-cerebral daughter. The hatred of intellectuals is a common phenomenon. Daphna didn’t know how to cope with it, and was looking for me to help. Her friends were eager to show her kindness, of course, but she desperately needed someone who could understand -- someone to empathize with her.

“How’s your relationship with your mother?” She asked innocuously.

“I suppose I’m the beloved son,” I answered. “She certainly doesn’t hold back her love – it’s probably even excessive. It’s a problem when a mother feels so much love that she forces her way on a child, no matter what he can or wants to do.”

Daphna looked at me with what was clearly envy, and as she began taking off her shirt she said, “I’d be happy to exchange your life for mine. Even here, everyone seems to be against me.”

“The skirt also,” I commanded, and she obeyed.

We were fifteen years old then. I was already determined to leave Hadassim at the time; Daphna wasn’t going to keep me there, for sure, though I was happy to pursue the dance of love in the meantime. I was reading Plato’s Dialogues, where I found the notion that truth could be found through love. I still hadn’t learned that Plato was referring to love between men.

As she lay there next to me, naked, Daphna told me that I was ugly. Naturally, I asked what could attract her to me, assuming she was telling the truth. She answered with a wry grin; she was still bitter at me -- she wouldn’t forgive that I wasn’t reflecting her in my eyes. As we sat naked together on the lonely sickbed, staring at the stars, we said no more that night.

At four in the morning we came back into our building in Unit E, disappointed and dejected, and we parted without saying goodbye – she to the girl’s wing, and I back to the common room. I knew that she deserved to be happy, but she was absolutely livid. Happiness is the very peak of an “I-Thou” dialogue, so the people who qualify as truly happy are genuinely few in number throughout the whole country. That night was a lesson for me that the dance of love is a precarious one; that it can lead to great sorrow as well as happiness. The dance of love doesn’t allow for a middle ground. At the same time, one would have to sever one’s own wings to avoid causing pain altogether; and then there would be no mountains, no chance of peering at the big bang and surviving a big fall. A middle ground would merely serve as our graveyard, which our enemies would happily replace with a small lot once they’ve conquered our lands.

As I sat down in the common room, I grabbed a copy of one of the “Davar” newsletters spread out over the table, and began writing a kind of summation of what life had taught me.

A crazy man can also cry Though his cry is more a groan And his tears don’t taste of salt But who will taste an insane tear? A pitch dark street

In the sober-minded sleeping city

I know it well,

We are old friends

The pavement is too hot

To be the man’s bed

And the light post - His pillow.

A crazy man can also dream

And his dream is simple and ordinary:

A woman in a gown and a couple of kids

And a smile not tinged in irony

But a voice can already be heard shouting: Crazy man, go away!

And hands pull on his beard.

His eyes are glimmering

His head is pulsing violently

He is forever chained

To a dream4.

When I was finished, tears were welling up in my eyes. “I’m not like the others. But am I really crazy?” I asked myself. Just then I felt the warmth of a body breathing behind me, and a hand cupped my shoulder. I knew it couldn’t be Daphna; her palm had always pressed hard and clumsily, while this one was soft and caressing. “Uri,” I heard counselor Shoshanna Lerner’s gentle voice.

Shoshanna and I shared a non-verbal , secret dialogue, one that continues to this day. She’d always seen the spark within me, and somehow I felt that she would always be faithful to me, come what may. This woman had also lived through the Holocaust, and back then I was already looking to understand the enigma of so horrible an event, to counter its future spread.

“Would you like to recite your poem to me?” She said. “It’s not a poem, really. It’s my testimony.”

At this, she kissed me on the cheek, and said: “All sorts of adventures still lie in store for you, I can see that…”

As I read out my lines, tears began gathering in her eyes, too. It was already six in the morning, so she led me back to my room for an hour’s sleep before wake-up call.

As I opened the door, Gideon looked up at me, wide awake. “Uri, where have you been, eh How many girls did you manage to fuck?” He asked, laughing uproariously.

“I fucked myself,” I answered.

I rolled from side to side in my bed, unable to sleep. I kept coming back to my misfortune, which in the final analysis turns out not to have been unfortunate after all.

I didn’t keep any of Daphna’s poems from those days. In 1975, she published a book of poetry for children. The title poem, which the book itself is named after, is, “Mrs. Frog cries in the bathroom.”

Mrs. Frog cries in the bathroom

Cries in the kitchen and cries in bed,

But if she stands unrivaled throughout her whole pond

In making an omelet

And though her cakes are always a grand success

And her house always glitters

And she is elegantly adorned

With every charm

Why then does she cry?

Who has all these and a lovely husband

And pleasure, too, from her dozen children

And also status?

Quite the autobiographical poem, no?

G. From Matzpen Till God

Arie Lavi, the gardener from the Achuza neighborhood on Mount Carmel in Haifa, brought up his son up with a leftist education. In the two years we had together in Hadassim, Gideon Lavi’s leftism wasn’t blatant, partly through my influence – the left is a manipulative parasite: it melts whenever confronted with heat. After I left, however, it was a whole other story. Though he disclaimed leftism during our recent interview, the nature of his political activism has been there for anyone to see. It was born of his father’s influence, of his friendship with Arie Bober, and without a doubt our own little philosophical-critical “club” at the school had its say on his development as well. He was subsequently active in Matzpen (The Israeli Socialist Organization) together with Arie Bober.

Arie Bober

Arie Bober was born to a poor family in Haifa, in 1940. His parents were actively religious, as his father served as a cantor at the synagogue. He was eight years old when his father died. Shortly thereafter, his mother sent him and his sister, Chava, to a religious boarding school, only to send back for them eight months later. After another few years, they were sent away again, this time to Kibbutz Kfar Ruppin as “outside” children (children who aren’t native to the Kibbutz, and have to be adopted by other parents there). According to his lawyer, Avi Bardugo, “His life started as a Greek tragedy – his mother gave him up and favored his sister. One day he discovered a document his parents had written up in preparation for their divorce (which became moot when his father passed away), in which he found that his mother intended to keep her daughter and for her son to remain with his father. When the father died, she gave all her attention to his sister, giving him up completely”5.

Gideon Lavi: “Matzpen was the ‘Sabra’ branch of the communist party, founded in 1962 by several dissidents of MAKI [The Israeli Communist party], who had challenged the leadership of Meir Vilner and Moshe Sneh. These included Moshe Machover, Oded Pilavsky, Akiva Orr, Aharon Bachar and Chaim Hanegbi, the latter coming up with the name “Matzpen”6. The principal aim of the faction was a solution to the Is raeli-Arab conflict and self-determination for all in the region. Their involvement with the social struggles in the country came later, with the Histadrut [the official trade union ] as the principal enemy. The Histadrut had consolidated its role as simultaneous employer, worker’s union, and mediator in trade disputes, and Matzpen wanted to found an authentic and independent trade union as an antipode.”

Arie Bober wasn’t so much a leftist as he was an ego-maniac when I knew him at Hadassim; he acted like the wisest man in the world, but he was willing to exploit his sexuality for political survival. He talked a big game, echoing all the leftist mantras, and at the same time he was surrounded by a whole slew of beautiful women, each of them under his spell. Metuka was one of them: “Arie Bober came to us from a Kibbutz in t he north, in the seventh grade. His experience was of a rejected child, as he had already been through several institutions. He had a surprising mastery of English; he was charismatic, an autodidact – a handsome and irresistible intellectual. I fell for his charm.

He’d always felt unwanted back home, always sent from one place to another; his family was always looking for a ‘solution’ for him. One byproduct of this, however, was that he had learnt more about sex than I could even imagine. An older woman had instructed him.

Nurit Gantz: “Arie was in love with women. He was a real gentleman: knowledgeable, engaging, always making an effort to endear himself. I wouldn’t put myself at risk with such a person, and he wasn’t my type anyway.”

Gideon Lavi: “He realized way back in Hadassim that he could make a living from various ladies’ devotion to him. Once, when we were hanging out, he mumbled something about all his women, how he had always prayed to have his way with them as a child but that ‘you should be careful what you pray for.’

“So there was always some besotted female worshipper willing to support him, to the point that he never became independent. He died while still indebted to half the world – most of them women, naturally. He tried to make his living translating some science fiction essays, and Ouspensky’s “The Search for the Miraculous” and the like. He replaced Marx with Ouspensky after he was thrown out of the party [Matzpen]. His new esoteric guru’s philosophy served his superman-complex well, providing him all the support he needed for his self-worship and illusion of personal growth. He radiated charisma, and displayed the propensity for being generous despite not having a penny to his name.”

In our view, Arie developed addictions to sex and mysticism as a post-tr aumatic reaction to abandonment. By a similar mechanism, his exaggerated charisma helped provide him with an illusion of his genius, as compensation for the early trauma. Clearly he wasn’t the only one to do this, in Hadassim or elsewhere; nevertheless, his personality and good looks made his later addictions add up to an idealistic icon in the eyes of his followers and worshippers.

It looks like Hadassim failed to neutralize Arie’s distresses – perhaps it was the fact that he only stayed with us for two years. The testimony of his girlfriend, Nurit Barmor, offers a glimpse into the source of his wounds, the resulting addictions and involvement in cults. The virulence of those wounds can be seen in the numbing effects of his behavior on his girlfriend.

Nurit: “I came back from Poland at the start of junior year, right after summer break, and immediately started seeing Bober after he stopped going with Metuka. We were in the same drama class, with Bomba Tzur, and we used to walk back together and argue endlessly. So there was an intellectual friendship there that led to an attraction, but he seemed like having sex with the brain before actually having sex, which was tiring.

“We had a lengthy relationship. He accompanied me to the harbor when I left for Poland again, and he was still interested in me when I came back; but at that point I’d already decided that our relationship was too demanding. I broke it off with him as he walked me back to my room, at two in the morning, and he told me he didn’t want it to end. Then he fixed himself on the grass outside my window and sat there where I could see him, to make me feel for him.

“He had a bitter streak, characterized by self hatred -- which subsequently led to the hatred of his people. He ended up involved with the New Left in the U.S., and we got in touch again when I became pregnant, after which he came to visit frequently. Around that time, there was one occasion when he came to pick me up from work and we started arguing about the philosopher Ayn Rand, whom he adored. He started calling himself an objectivist, and joined Uri Avneri in 1963.

“Bober had a rare intelligence; he was extremely gifted, but h is personality worked against him and eventually led him to start hating his people. His father was taken from him and his mother rejected him. She wanted to keep her daughter but not him.

“He wrote to me once that ‘my mother is more important than my matriculation exams.’ He needed validation. His intellectual activity was all meant to put him in the center of things. He got what he wanted as a history teacher; one of his pupils, Micha Shagrir, told me that they all greatly admired him. He was an eminently charismatic autodidact.”

Bober came to believe in the doctrine of the war between the Sons of Light and the Sons of Darkness, and became a good friend of Moshe Kroy. I met him around Kroy’s social circle in the philosophy department at the Hebrew University. His magnetic hold on people was a thing of the past; it was Kroy who was a kind of guru to him at that point.

Arie Bober and Gideon Ariel

Kroy was sharp enough to refute an argument without holding to a position of his own: his was the shallow kind of intellect that Plato had warned against when he’d forbidden anyone younger than forty from studying philosophy. The same danger holds true with respect to the Kabbalah. I remember telling Kroy, during one of his meetings, that he was moving toward a dead end and heading for a fall. Bober burst out laughing and said I shouldn’t be taken seriously, but Kro y only shrugged him off and pursued the argument with me. He seemed to agree that I’d found his Achilles’ heal. Later, I remember watching Kroy interviewed on television and nodding my head as he spouted that the Sons of Darkness where searching him out to kill him. By morning he had already disappeared, and his body turned up several days later.

Gideon Lavi had his own words regarding Arie Bober’s psychological dependency and its deleterious effects. “When Matzpen split, Arie Bober remained with the Tel Aviv faction. But even there he was bitter and was always quarreling with them, so they kicked him out. Then he went to Jerusalem, to Sharem Al Sheik, and took up with a girl there – until she’d had enough of him. So he moved on to the Shaar Hagay farm and quarreled with everyone there, too. Only Debora Ben Shaul would talk to him, and she even supported him for a while, until it was finally enough for her, too, and she threw him out. That’s when he came to Rosh Pina to live with me for a while, until I found a rent-free place for him. At some point he even started paying rent, at ten dollars a month. He made a little commune there, inviting people to stay on as his guests. It was the 70’s, when many of these communes became the thing in the North. There were marijuana plants all over the place then, as tall as Eucalyptus trees.”

The lawyer Lea Tzemel was his girlfriend for a year while he was still with Matzpen. She recounts: “With all his spirituality, he was still interested in power. He’d been able to tame his appetites and live in poverty – he’d only eat a little bite of something here or there, add lots of marijuana and that was enough. But he still kept his tongue sharp and his criticism biting. He was an ardent student, and he loved teaching – the younger generation was important to him. They followed him around like their guru and he woul d read to them and enthrall them with his speeches. You couldn’t deny that he had undergone a serious transformation: from an urban bohemian type to a man of nature. He’d show me some new beautiful thing every time I’d come for a visit; there was definitely some kind of inner struggle, some fundamental change in him. His conversation turned from politics to spirituality and God, and in the end he leaned toward the Jewish religion. He was still healthy when I saw him on one of my last visits, and I remember hearing him say he wanted his daughter, Gaia, to see the Simchat Torah ritual at the Synagogue. I was shocked .7”

We, on the other hand, weren’t shocked at all. Bober embodied that distinctively Israeli metamorphosis of the Frankfurt school and the Mount of Truth -- the inevitable jolt that happened when the rupture in the Israeli left between mind and body, the materialist Marxism of Matzpen versus New Age spiritualism, could no longer be contained. It was clear to us that Arie Bober and his friends in Matzpen were the spiritual children of Martin Buber and his following in the Talbieh School. Yossi Beilin, along with his friends in 2006, is merely one more branch of the same family tree. It’s reasonable to assume that Arie Bober was drawn to the Talbieh way of things by way of a distressed childhood and severe emotional abuse. It shows something not only about him but about the school, as well as the origins of its power.

Let us now turn from our sad promenade on the life of Arie Bober to Gideon Lavi’s first political footsteps.

Lavi: “Arie Bober served as a sabotage quartermaster in the navy while he was a chemistry student at the Technion [Israel Institute of Technology]. At some point he’d had enough of Haifa and transferred to Tel Aviv. He became friendly with Nathan Yelin-Mor, the editor of the magazine Etgar [“Challenge”], and one of the three ex-LECHI leaders, as well as Gabi Lachman. Both of us worked as technical assistants on Etgar’s editorial board, so we weren’t contributing any essays. But we knew that Uri Saar, the critical editor, was the same Uri Milstein who was studying philosophy and economics in Jerusalem at the time.

Arie was very jealous that Uri was publishing his essays together with Uri Avneri and Amos Keinan – it upset him to have to settle for the role of Nathan Yelin Mor’s messenger boy. Uri Avneri was the financial backer for Etgar. Haolam Haze [a Israeli periodical] inspired us. Nathan Mor was an important man, and we were willing to work hard just to remain in his presence. We wondered how Milstein had reached a position of equality with him on the magazine.

“Working for Etgar gave me the opportunity to meet Chaim Hanegbi, an offspring of the venerable Jewish community of Hebron. He liked to claim that Hebron was his personal possession.

“Matzpen was just the sort of movement Dostoyevsky memorialized in The Devils. The setting: thirty ideologically armed men – sitting in a small room, talking. The group published a book, Peace, Peace and There Is No Peace, under the pen name “A. Israeli,” where we reiterated all the repeated efforts by Arab countries to make peace while our leaders rejected them time and again, secretly, apparently because they considered it contrary to our interests.

Chaim Hanegbi won Bober over to Matzpen with a good cup of coffee. I followed him there to see what it was like, and what I found was heated political talk and flier campaigns. And yet, what was written in Matzen thirty-five years ago is the language of discourse today: two states, for two nations. That’s where the ideas came from. A bunch of Trotskyites, and nice girls with provocative dresses – an alternative to the unfeminine, pioneer-like women’s fashion of the day. Sexually we were still puritanical, however; the focus was on politics -- the clothes were merely decorative.

There was no sense of humor in Matzpen. We were hard-lipped Trotskyite Marxists; we read Chinese newspapers. Our spiritual ancestors were the Talabieh men, especially Martin Buber (who was nothing like Bober).

And so it continues: we are the spiritual ancestors of Peace Now [the Israeli Peace Movement], Yesh Gvu l [“There Is A Limit”], the group that has shouldered the task of supporting refusenik soldiers, and Four Mothers. Even Arik Sharon ultimately came around to our view. We won.

H. The Learning Disabled Child Becomes an Educational Wizard

Gideon Lavi was born in Haifa in 1938, to Arie and Miriam Lavi. His parents had emigrated separately from Germany only four years earlier, right after Hitler’s climb to power. Arie had trained to be a gardener in Germany, and that’s how he made his living in Haifa. He was a fifth-generation German in an assimilated, secular family that had embraced Zionism. Arie had already come to Israel prior to WWI with Hashomer Hatzair, on a pioneer stay at the Kibbutz Maoz Chaim in the Beit Shaan Valley, but realized soon enough that the lifestyle didn’t suit him.

In 1942, when Lavi was only four, his mother died from Typhoid fever. Arie had rushed her to Haifa’s British medical officer and begged for antibiotics to save her life. The man answered: “You make me laugh. There are soldiers wounded in battle who’ve waited four months for this.”

Gideon Lavi

Gideon Lavi can remember the constant sound of Beethoven and Brahms on the kitchen-radio; he remembers sitting on the high chair, his mother busy cooking something on the stove. Listening to music – especially chamber music, where dialogue is such a crucial factor – would occupy him for the rest of his life, and enhance his mind. It would help him when it came time to understand Carl Jung’s language of mythology, which he read in the Kibbutz library of his youth. It would help him understand the languages of chemistry and physics later on and into adulthood, and even help him season and prepare the different mushrooms he collects in the woods of Rosh Pina today.

Lavi: “My first foster family was rather unconventional, and helped to add unique components to my “outsider” mentality, beyond the fact that I was an orphan. My father handed me over to a woman whose husband had returned to the Soviet Union for ideological reasons, and where he was living out of wedlock with a communist train worker. My foster mother lived on the edge of Kiriat Chaim, close to the train station, and raising children was her livelihood. There was bright big picture of Stalin right there in the living room. I used to hang out in the courtyard and play with the other neighborhood kids. One of them was Alisa Gur, who grew up to be Israel’s beauty queen. She was already beautiful back then, and she taught me what love was.

“The train station was a big attraction, and every Saturday we used to run next to the train and send it off to Beirut waving our handkerchiefs.

“When I was six, my father whisked me off from Rosh Pina and dragged me off to a religious boarding school in Kiriat Bialick. I didn’t like the environment there, and it didn’t like me, either. I mastered reading and writing before all the others, so I was bored the rest of the time.

“Two years later, I was settled in with a foster family and a secular school. This was during the period of the War of Independence. I was an eye-witness to a bombardment of an Arab munitions convoy moving between Kiriat Motzkin and Kiriat Bialik; every last window in both towns was shattered in the explosions.

“Physical abuse was my new foster family’s stock in trade. When my father found out about it he quickly moved me to the Kibbutz Ein Hashofet, which was a step up, but still no great pleasure – I was the “outside kid.” The kibbutzni cks thought they were sons of gods, which meant that I was practically invisible. But there was a good library, at least, so I spent a great deal of time reading, mainly about mythology.

“When my father realized I wasn’t doing too well in the Kibbutz, he decided to take me back home. He was remarried about the same time, but the marriage failed after only a few months – partly on my account, I’m afraid. I felt terrible at my new school in Haifa, where the educational counselor soon advised my father to place me in a learning- impaired school in Pardes Hanna. That place didn’t even have electricity, and most of the kids there were Morrocan immigrants who built up their own protection racket. I endured it as best I could until the ninth grade, when I finally moved to Hadassim.”

When Lavi arrived in Hadassim, he was classified as developmentally disabled. But the label didn’t make any impression on me or Daphna, or Arie Mar. In our eyes, Gideon Lavi was a sharp kid, worthy of conversation. He was a perfect fit for Hadassim’s educational conception, as embodied in our little circle, which combined existence and knowledge, values of discipline and improvisation – the combination of intellectual inquiry and playful dialogic creativity that power the spirit of Plato’s Symposium. It was a model without which Einstein’s creative process would be incomprehensible. 8

Hadassim was a hotbed for the kind of cultivation that was needed for Gideon Lavi’s rare precocious abilities to flower. The fact that it allowed for those abilities to redound to our benefit is illustrated by the following story.

Gideon Ariel: “I was looking for friends at the time, and Gideon Lavi became a good one. He was the best chemistry student – while I was the best thief. Lavi asked me if I could somehow steal some Sodium and sulfur, and with his help I ended up getting a nine [on a scale of 10] in chemistry. So while we certainly pulled it off, we almost exploded into little bits in the process: I suggested that we shoul d build a laboratory of our own . We co-opted an old Arab house, and I went off hunting for tables and minerals. He told me everything we needed, and I stole accordingly.

‘I’ll show you how to make nitro -glycerin,’ Lavi told me.

“We worked on it all morning. Two hours later, when we were done, he tossed away the heated test-tubes -- and the house exploded. We were lucky not to explode ourselves, which would have happened if the tubes had remained in his hands. The destruction was horrendous; we ran away as quickly as we could, and somehow lived to tell the tale.”

When I came back to visit Hadassim fifty years later, I discovered, near the stables, an old Arab house with broken, soot-covered windows, the last remains of that explosive incident. Some people, unlike Daphna, are willing to play and explore, even if it endangers their lives. There just isn’t any other way to be human.

When he was finished at Hadassim, Gideon Lavi did his bachelor’s in Chemistry at the Technion, and subsequently worked as nutrition engineer and Chemistry teacher in the Higher Galilee, where he guided hundreds of students through the subject. The learning - impaired child had become an educational wizard: every last student of his passed the matriculation exams. None of them required “special education,” since they were being taught by a man who embodied the Hadassim spirit.

I. “It’s Still Open Season on Us”

Nadiv Weisleib arrived in Hadassim from Netanya in 1954, the year I brought the Lamed Hei to life. I’d dedicated hours upon hours to studying Israel’s wars (the War of Independence in particular) through reading and in ongoing conversations with Michael Kashtan, Arie Mar and Gideon Lavi. Nadiv was three years younger than me. Danni Dasa and Gideon wanted to enlist him in sports and he seemed interested, but that didn’t rouse him from what seemed like permanent sadness. When I asked him to become a research assistant in my project, however, he reacted with uncharacteristic passion. I assigned him the task of summarizing all the books dealing with internecine violence between all the underground factions in the run-up to statehood, and evidently I’d hit the bulls eye. Those very struggles were engraved in his identity, and they were the root cause of his sadness.

Nadiv was born in 1943 in Tel Aviv, to Yoseph and Yehudit Weisleib. The family moved to Netanya after a few years. His father was a LECHI activist, and had to stay on the run both from the Hagana and the British authorities. Yoseph would hide with his friends in the citrus plantations of Raanana while the police searched his South Tel Aviv apartment.

When he found out he had a son, he wanted to name him after his father; his friends, however, begged him to choose a name from a Zeev Zabotinsky’s Beitar poem, “Gaon, Nadiv Veachzar” (“Excellent, benevolent and cruel”). In mid-September of 1948, when LECHI partisans murdered Count Folke Bernadotte, the Swedish UN mediator, in Jerusalem, Yoseph (along with several others) was arrested and held in prison without trial. When he was released, he drowned at sea on a trip to the beach with his wife and child. Nadiv was only six years old.

“My mother didn’t keep in touch with the LECHI people. She clearly wanted to keep quiet to me about the underground struggle,” says Nadiv. “She felt abandoned, frustrated by the lot she was dealt in life by sticking to my father. She made very little money as a social worker assigned to new immigrants, so our situation at home was pretty dismal. She worked all day, and I spent my time on the streets. By the time I reached the sixth grade, the Welfare Bureau decided to send me to Hadassim and subsidize my tuition and residence there.

“I was an outsider there. I’d come from a traditional family, and now all the teachers and counselors were secular, most of them leftists. Even many of the students were Marxists, while I was very right-wing. Still, my situation in Hadassim was good; no one forced anything on me – I was free to think and do what I wanted. It was home, with a warm bed and good food to eat, which was a far cry from my mother’s house. Rising up at dawn and going to work was wonderful.

“When they forbade us from going to the Independence Day parade in Tel Aviv, I organized a strike: I simply couldn’t imagine myself missing the parade. So I informed Rachel Shapirah, in the name of all the students, that we would abstain from the village’s celebrations. But I gave it up, eventually.

“I became active in sports: I joined the village football team; I became a swimmer; I ran long-distance. Participating in athletics helped stabilize my personality and built up my self esteem. That didn’t change the fact that I was an alien in any society where people like Martin Buber and Arie Bober are taken as the standard. That feeling remains with me today: the culture and media in Israel is predominantly leftist, so nationalistic Israelis are almost seen as illegitimate.

That, in my opinion, is the true paradox of Zionism and the State of Israel. I guess it’s still open season us.”

J. A Young Delinquent Achieves the Summit of the Legal Profession

Nahum Feinberg is one the finest Israeli lawyers, a first-rate specialist in the field of labor relations. But his was a transformation from a near-criminal to a high exemplar of his profession, and it began with Hadassim.

At the age of ten, Nahum was on the verge of being sent to a juvenile institution. His bemused parents, Amnon and Tzipora, feared that their son would only dig himself further down to the netherworld of crime in the institution. Luckily, the father was a senior government official, a man who discussed Plato with Ben-Gurion himself. Amnon Feinberg managed to delay his son’s transfer to the juvenile institution, securing an agreement from the police that Nahum would be allowed to enter Hadassim instead, for a trial period.

Nahum Feinberg

“Hadassim probably saved my life. I was walking a thin tightrope at the time, one that would have led me farther down the road to crime,” Nahum concedes.

Amnon and Tzipora immigrated to Israel from Russia in the 1920s. Both came from orthodox families but had left religion and become atheists. They even passed on celebrating Nahum’s Bar mitzvah, something he regrets to this day. They were married in the early 30’s and built their house on Tel Aviv’s dunes. Opting for security, both availed themselves of membership in the Histadrut and joined MAPAI (the Zionist- Socialist party). Amnon initially worked for the Mandate government, but was later appointed to the positions of director-general of the farmer’s union and registrar for the community cooperatives (both on Mapai’s recommendation), while Tzipora was a secretary for the labor union’s health fund. They were never committed socialists, but Bolsheviks they were indeed.

Amnon was a tough man, but according to his son he was quite gifted, almost a genius – despite his lack of formal education. However, that wasn’t a cure for an unhealthy tension between the parents, one which made it hard to raise a trouble-prone child. Nahum lacked the vital intimacy he needed as a child at home. On the other hand, the parents were proud of their older daughter, Simma. As Amnon puts it, she’s a conventional person who went through the usual “Sabra” life course: participation in the youth movement; teachers’ seminary; a teacher; a happy family.

Nahum Feinberg

Nahum Feinberg was born in Jerusalem in 1944. Subsequently, his parents moved to Tel Aviv and discovered, to their horror, that their son was uncontrollable. The tallest kid in his class, he was hyper-active, contemptuous of study, always ready to fight his friends – a genuine bully – and an indefatigable destroyer of property, “clockwork orange” style. And that was only in the first grade. He drove his mother crazy. She kept repeating: “If you don’t want to listen to me you can get the hell out of my house!” Nahum took her quite literally: he climbed to the top of a tall tree in the garden and hid in the branches the whole night, looking on, amusedly, as his parents, the neighbors, and finally the police searched everywhere for him. He was only satisfied when he saw his parents beginning to lose their minds from worry.

Nahum: “Back then it was called a ’street kid’. In my case, they called me ‘key kid,’ which meant that both my parents worked hard to feed the family. That was what ‘middle class’ referred to back then. To their credit, it should be said that they did all they could to bring me up in a worthy home, but it’s clear they didn’t know how.

“My favorite sport at the time was sticking bean cans underneath buses at the station, to ruin the passengers’ clothes once the bus got moving and the wheels burst the slippery contents in every direction. When I wasn’t doing that, I was often hurling pine cones at people from the roof using my own slingshot.

“The throw that finally broke the camel’s back happened when I was nine: I decided to take one of the trucks parked on the street for a ride. I managed to drive it a few feet until I hit a wall. The police told my parents that I would have to be transferred to a juvenile facility, but they eventually compromised and let me go to Hadassim instead.

“To this day I find it hard to grasp how I survived those days at all, or how my parents could continue to love me with all the trouble I gave them. I know that their decision to send me to Hadassim when I was only ten was the right decision, and must have involved emotional sacrifice – not to mention the expense, since I wasn’t being subsidized by Aliyat Hanoar [the department of the Jewish agency charged with educating Holocaust survivors] or the welfare Bureau, as we weren’t poor enough.