Book.

The Oasis of Dreams

Chapter 5. The Princes

Part Three: Our Teachers

Rachel and Jeremiah Shapirah, the founders of Hadassim, knew they needed the right caliber of teachers if they were to succeed in their unparalleled experiment and implement the philosophy of dialogic creativity they’d inherited from Schwabe, Buber and Yehoshua Margolin. They needed people who themselves fit the dialogic ideal and represented the upper crust of their fields. Indeed, that’s what we got: our teacher team fit the mold in spades, and it was that airtight fit to the vision of Hadassim that was the secret of their success, and ours.

Part three is about those teachers; about the dialogue between us, the students, and the adults in the village. It is the story of the educational fruit borne of creative dialogue. Though there were dissonances here and there, as in any organization, these blemishes took nothing away from the fact that our teachers had abstained from personal promotion, foregoing any chance at a national or international career. We were their sole promotion and career; our care was their calling.

We will tell the story of our dialogue with Nature, via Avinoam Kaplan; our dialogue with Art, via Greta Salus, Danni Dasa, Gil Aldema, Gari Bertini, Tzvi Rafael and Moshe Zeiri; our dialogue with Athletics, via Danni Dasa and Tomi Shacham; our dialogue with the emanations of the intellect, via Michael Kashtan and Shalom Dotan. Finally, we will tell the story of the dialogue we experienced among ourselves, facilitated by Danni Dasa, Shevach Weiss and Arie Mar.

It is doubtful whether such leadership as the Shapirah’s, or such a complete harmony of abilities and spirits as they had in their educational team, had ever existed before. Wherever someone may one day wish to imitate the Hadassim model, these will be the type of men he will need.

Chapter Five: The Princes

A. The Prince

The chronicles of princes, Aristotle taught us, attracts the plebian readers who wish to peer into the bedrooms of the world’s nobl emen. People seem inherently drawn to the decadent histories of British royals, from Edward VII to Princess Diana, or even to such august banalities as Bill Clinton’s affair with Monica Lewinsky. Princes reside on the mountain peaks – and when they fall, like Oedipus, they fall hard and low, down to t he farthest abyss.

If there was ever a prince in Hadassim, if there was ever a member of royalty within our democratic and pseudo-egalitarian mini-culture, it was Micha Spira. He was a grandson of one of Hadassim’s spiritual founders, Professor Moshe Schwabe, rector of the Hebrew University, and he was the son of Professor Eliyahu Spira, the man who founded the orthopedic and rehabilitation departments at Tel Hashomer, Israel’s biggest hospital, and an originator of a new method of bone rehabilitation. For his part, Micha was thirty-seven when he became full Professor of Brain Sciences and dean of the Faculty of Natural Sciences at the Hebrew University, and one of the world’s leading scientists in brain research, the principal new burgeoning medical field.

But Micha was not only a prince by virtue of birth; his virtue was one of character, as someone who refuses, consciously or not, to conform to the general norms, paving his own way and his own rules – rules that could only be grasped, in their full exceptionality, through dialogue with him. There were two women we know who joined him in that dialogue: the princess Ofra Shapirah, and the Cinderella Shoshke Grinberg.

Professor Eliyahu Spira

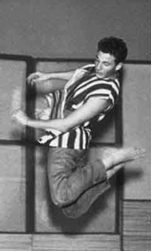

Micha’s dance steps were a unique language, one that spoke directly only to him, b ut nevertheless shone through indelibly in his movements. It was something that touched everyone, and he was considered a genius for it. True geniuses can hold a super-dialogue of that kind only with themselves; others can only admire it, even if they don’t really understand. The great Martha Graham, a genius in her own right, was shocked into submission while observing him dancing. Micha rejected her invitation to join her own troupe: a true prince never joins a pack, though he surrenders to an inevitable loneliness.

Micha contributed to the Hadassim community the display of his aristocratic magnitude, the likes of which most students wouldn’t dare dream about. He adopted for himself the toughness that characterized the children of the Holocaust and distress, a key ingredient in his rise to worldly heights. Whether by brute luck or through some mystical connection, I made my own contribution to his development in Hadassim. Neither of us was aware of it until I interviewed him, not long ago, in Israel’s most advanced laboratory for brain research (and one of the most advanced in the world), which he directs. His study of the regeneration of damaged nerve cells constitutes the state of the art for today’s medical research.

Micha and Ofra (his girlfriend and subsequently his first wife).

I was unaware, in our Hadassim days, of the real noble and princely qualities of Micha and Ofra (his girlfriend and subsequently his first wife). In Hadassim, the model for a true prince was found in The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: Naïve, benevolent and an incurable optimist. That’s what everyone expected Micha to be, that was the erroneous lens through which his actions were inevitably going to be judged. At the time, my own view of the “prince” stock figure was found in the Renaissance Medicis of Florence, to whom I was introduced by Machiavelli. So I thought Micha and Ofra were wasting their time on dancing. I tended to look down on both privileged “princes” and dancers, viewing such people as poseurs; I’ve spent most of my life exposing the cleverly disguised faces of pseudo-princes and other various frauds. I’ve therefore stood in sharp confrontation with most people, few of whom are princes and many of whom are slavish followers.

But the reader will be impressed with how exceptional a prince Micha is, with all his strengths and weaknesses. Indeed, Rachel and Jeremiah had it in mind to draw people like him to the village, to add to the virtue of the other children. They didn’t always succeed, and I wasn’t terribly happy with his integration into the village myself – I wasn’t there to be further instructed in virtue – but his presence nevertheless fulfilled its ultimate purpose. Even if I didn’t know it at the time, I did finally learn it when I truly, and happily, discovered him for who he is in 2006, fifty years later.

Micha was born in Tel Aviv in 1940 , on Gordon Street, not far from Reines Street – which was Gideon Ariel’s neighborhood. Gordon and Reines streets were rival camps, with rival gangs, so it’s reasonable to assume the two kids weren’t exactly friends at the time. Apparently the Reines group was a little rougher and plebian, while the Gordons were higher up the class ladder. But a common denominator held between Micha and Gideon: they both hated their elementary schools, their overly strict teachers, the rote memorization routines. I met Micha among Gideon’s friends and “foes” during one of my visits, so that the seed for our future dialogues was planted then, maturing in this book. Micha was spoiled, Gideon was roughed-up, and I was rebellious: each of us ended up in Hadassim for those individual reasons. At the turn of the fifties, a time when Dizengoff St. was Tel Aviv’s intellectual and spiritual core, we used to hang around Kasit Café and absorb the spirit of those poets who were that generation’s teachers -- Natan Alterman and Avraham Shlonsky – a spirit of creative individualism. This spirit reigned also in Hadassim, and blossomed within the three of us, manifested in three different fields: brain research, history, and Biomechanics.

The fire of Normandy finally lit in Micha’s eyes in 1944, when a gigantic explosion rocked a building near where he and his friends were playing.1 Two of his friends were killed, and he was eventually rescued from out of the ruins, worn and wounded. The trauma of nearly being buried alive has accompanied him ever since, and we speculate that it was at that moment that a new man was born – Micha the dancer. Though it’s not something we can prove, we adopt the explanation because it was in the very same year, and in a similar process, that Hadassim was born – born in a way that the mind struggles to grasp – while Micha himself was destined to become one of Hadassim’s pearls.

Micha joined the fifth grade class in Hadassim at the age of eleven, after four years at the Carmel school in Tel Aviv. His younger brother Gadi, later a professor of Biochemistry at the Technion, came with him to the village.

“What is your story? Why did your parents send you to Hadassim?” We asked him. “Why did your parents give up their right to raise you, even after you were almost taken from them at the age of four? Why did you forgo the advantage of their bosom? Life with Professor Spira and Professor Schwabe certainly seems like it would have been more interesting...”

Micha: “I’ve wondered about that many times. There really is something unnatural there, that parents as established as mine would let their dear son grow up in an outside institution. In looking for an answer, I was operating under a few assumptions. For one, my parents told me that they’d sent me to Hadassim because it fit their idealistic concept of education. It wasn’t easy for me to accept that as the real reason at the time. Maybe they were quarreling too much and wanted to distance me from the home, I thought.

Many children in my position would have felt hurt and victimized, to be deprived of such a home and sent to a boarding school. I didn’t feel that I understood it completely for many years, until I finally came to understand where they were coming from. Theythought the Shapirahs had come upon a magnificent educational vision, including a respect for children and an authentic respect for education as a process and tool for understanding rather than the tortuous mass of data that the schools of our day were inflicting on us. They were attracted to Hadassim’s respect for independent thought and creativity, as they were shaped by the same man whose philosophy the Shapirahs had implemented -- my grandfather [Schwabe]. So their answer to me at the time was genuine.”

“What was the concrete event which brought you to Hadassim?”

“In the summer of 1951 , after I’d finished the fourth grade with lackluster grades and my mother and father were abroad, I was sent to the summer camp in Hadassim. I came, I saw and fell in love with the place, especially its atmosphere.”

“What was so attractive about it to you? What was there that you didn’t already have in your parents’ home in Tel Aviv and at the Carmel school? You couldn’t have wanted for anything, coming from such an elite family?”

“Nothing was missing at home. My parents were really the ideal kind. Grandpa was like a good friend, telling me stories that actually helped me develop mentally – as opposed to the Carmel school, which I hated. It was a conservative school of the worst kind, with regard to both its teachers and methods. I’m very much the rebellious sort, so when I hate something I hate it in the maximal sense. There were things to hate in Hadassim, too, but it was great fun in general. I used to study in bare feet in my not-so - tidy room; we’d call our teachers by their first names; and I had wonderful friends who could really understand me, and who I could identify with. The Hadassim of 1951 was the closest a kid could have to the Garden of Eden.

“When my parents got back to Israel from their travels, I told them I wanted to stay in the village. My mom resisted at first. My parents believed that the proper education for Europeans was to be found at home – a boarding school was only meant for aristocrats. Father had men like Ben Gurion, Ezer Weizmann and Moshe Dayan for friends; he considered himself a socialist, a social egalitarian. That was the fashion. I needed my grandfather’s help to persuade my parents to let me go, and they eventually yielded. Unlike the other kids, I was free to come back home, and would have been received with open arms. But the school year soon began, and I wasn’t disappointed at all with what I saw. We were learning how to learn.”

“There was farm work to be done in the afternoons, and I found it immensely pleasurable. I strapped horses to carriages, and led them back to the village, carrying loads of eggs. I loved the girls and they loved me back. I remember several of them especially: Zafra, who was adorable; Yardena, who was a real beauty, and Iris, who was both stunning and an athlete; and Mushi, who really felt strongly for me. Not a bad way to live, really. I was a true prince: my parents were like family to the directors, for whom my grandfather was something of a guru.

“Life in the children’s community crystallized me as a human being. Most everyone who was there owed their success to Hadassim; certainly there are different levels of success in life, but no one came out of that place a loser. We were taught how to solve problems, how to confront life’s difficulties, to communicate, to fight to better ourselves. It was a school for life – for the whole of life. It was tougher existence than what we would have had in our homes, with out parents. I was just a little boy, and I had to deal with Yehudit Frumin, our unit counselor, who used to greet us at six in the morning with her screams of ‘Up! Wake up! Good morning!!’ There was no motherly tenderness; no one could say we were there to be spoiled. We had to make our beds like good soldiers. We grappled with loneliness. At home, you run to your mother and bask in the cool shadow of fatherly advice – in Hadassim you were on your own. But my bond with my parents remained intact. My father had a car, of course – though it was a rare possession in Israel at the time – and my parents would come over frequently and spend hours in the village. So I got to enjoy both worlds: I was fortunate to have a solid and good home, and to be forged as a man in an ideal socializing environment.

“In the eleventh grade, I was thrown into a personal confrontation with the teachers and directors. I had to fight them, and apparently they really went after me – especially Rachel, Jeremiah and Shalom Dotan. Despite what was supposed to be a perfectly egalitarian value system, I was still perceived as ‘upper-class,’ so they felt they had to prove their power over me. The story was one of mutual frustration. In a burst of youthful indiscretion, one day I let it be known that I thought Hadassim’s teachers were pretenders and weaklings – that they couldn’t measure up to life on the outside, and had retreated to life in the village to hide their ineptitude. It was characteristic of an adolescent who’s in complete rebellion against his environment and wants to change the world, and it was appropriate – it’s always appropriate and never appropriate . It eventually got back to the directors that I’d said this, and they were already looking for a pretext to expel me ever since they’d suspected that I was sleeping with their daughter, Ofra – who later became my first wife.

“It wasn’t long before I was summoned, in the middle of one of Arie Mar’s chemistry lessons (incidentally, one of the greatest teachers I’ve ever had), to appear before the entire management of the school. I came into the offices and the secretary showed me to the conference room, where I was surprised to see the entire slew of teachers joining the directors in what was basically a court martial of sorts. They all sat together, in half- circle formation, with Jeremiah and Rachel at the center, facing the chair of the accused/condemned. I couldn’t help but laugh at their stony facial expressions. Even my parents had been summoned, to sit idly by in the corner.

“I said ‘Shalom!’ and took my seat. Rachel, in all her arrogance, announced that the pedagogic board had decided that I would be expelled unless I apologized for my comments about the faculty. Those were the heady days of James Dean and the ‘Rebel without a Cause,’ and I was boiling with adolescent mutiny. So I just sat there for three minutes, without saying a word. Finally I raised my brow scornfully at Rachel and Jeremiah, rose from my chair and said, looking at my parents, ‘We’re leaving.’ They got up and hugged me, and we began to step out together – and then the storm erupted. ‘This is unacceptable!’ Rachel yelled at us. ‘Sit Down! Spira, sit down!’ Others were also screaming -- it was bedlam. I had nothing to say to them. I just looked up at my parents and reiterated, ‘We’re leaving now,’ and we walked out on the ‘Courtroom.’

“I stayed home for two weeks, taking in suspense novels, when someone from Hadassim called and asked that I return. It was an apology of sorts on thei r part. The First Fruits Festival of Shavuout was coming up, the pride of the Shapirahs. They knew that they couldn’t do it without me, as the festival primarily involved the dance troupe. For my part, I wouldn’t have come back if it hadn’t been for the dance troupe, either.”

“Do you think you were right?”

“If that’s how I expressed myself, that was just how I felt at the time. It was youthful rebellion on the one hand, and on the other it reflected the decay of Hadassim’s educational ideal. There’s plenty of room to disagree with the way I handled it, but they’re attempt to expel me was totally unjustified. Hadassim was starting to lose its character as an institution that prized creative dialogue. Rachel and Jeremiah were going through their own entropy, and the insults I threw at them weren’t 100% on the mark, but they definitely contained an element of truth. By the turn of the sixties , there were teachers streaming into Hadassim not for any ideological commitment or educational mission, but because they felt they had to resolve their own personal issues. Even the dance instructor I loved so much, Greta Salus, had come partly to solve her own financial problems. They weren’t all pure souls. Hadassim was becoming worn out, and its educational conception eroded as it integrated with the state educational system. All of a sudden, state mandated matriculation exams became a critical issue. Schools were being valued in terms of their students’ success in those exams, and the Kibbutzim, which had disregarded conventional norms for years, were waking up and realizing that their adults weren’t going to integrate into the nation without formal education and without being part of the establishment. The educational process was left to flicker in the background

“I was a mediocre student for the most part, and that contributed to an intense clash with Shalom Dotan, the bible and history teacher. In the eleventh grade he told me that I wasn’t fit for university studies, and suggested that I leave Hadassim and study gardening. It was an unbearable blow for my ego. I was quite captivated by his subject – he taught the bible from a historical point of view – and I loved his presentation, too, but he absolutely hated me. My grades in his class wavered between 5-6 most of the time [out of 10]. When I heard there was a possibility of doing a final paper in lieu of the bible matriculation exam, I decided I wanted to do a final paper in biology to get out of Dotan’s final exam -- though it meant I had to do very w ell on an another upcoming test of his. So I studied as hard as I could: I went home and buried myself in Proverbs, Pslams and the Book of Job for several weeks. It got to the point that I knew them by heart, Casuto’s commentary and all the other essays on those books included. Finally I took the exam, and waited days for the results. When I got it back, I saw that Dotan had given me another 6.

“I was a grown young man, strong and hotheaded, full of righteous fury, and I ran like a lightning bolt over to Dotan’s house and demanded: ‘Let me see the Test! Hand it over! ’ But he refused. So I threatened him: ‘If you don’t let me see it I’ll call the police and accuse you of fraud, and you’ll be sent to jail.’

Finally he gave in, tossing the bit of paper over from across his desk.

“I’d already decided I was going to hand it over to the directors and demand that it be checked and rescored by three other teachers. Rachel agreed to this, and when the test came back to me with a grade of 9, I realized that Dotan was a bastard – and lost my faith in my other teachers.”

Shalom Dotan

Shalom Dotan: “It was fifty years ago and I don’t really remember all the details. I was wrong about Micha. His Hebrew was weak – filled with spelling errors. He was quite arrogant, but his papers were bad. So I felt accordingly that he wasn’t fit for academic study. I don’t really remember that story about his exam, that business about the higher grades from other teachers. All I remember is coming back home from Tel Aviv one Friday and wanting nothing better than a bit of rest, only to have Micha barge into the house demanding to be retested at once.

“The next time we met it was 1982, in a rally against the occupation of Beirut in Jerusalem. Our conversation was actually quite friendly. I’d say that what he told you in his interview by and large corresponds to reality.

Micha sums it up: “In retrospect, it’s clear that Shalom Dotan was unethical, at least in his approach to me. The proof is that I finished my bachelors and masters degrees with honors even before my military service. I’d already started my doctorate, and by the time I enlisted I was already half a doctor. I graduated from the officer course with full honors and became went on to become company commander in the engineering corps, finishing as captain of my reserve unit. I was promoted to major but refused a later promotion to lieutenant colonel. All the while I was facing disciplinary hearings every week for refusing to wear the military beret.

“If Dotan could make such a huge error in judgment in my case, you can imagine how many other teachers made other such mistakes with regard to countless other students, and the damage that must have done. Ultimately, Dotan’s misstep with me didn’t hold me down – it got me angry. But how many others students were held down by his utterly distorted and overly negative appraisals?”

“How do you weigh Hadassim’s contribution to your career, from your vantage point today? With all your academic achievements?”

“For me, it’s a story of being born with a silver spoon in my mouth and being forged into something else in Hadassim, where I was treated as only one of many, equal in rights and responsibilities to the Holocaust children and the more underprivileged. Living together with them gave me firmer character roots, but at the same time it compensated me for my lack of family intimacy.”

Nurit Barmor gives an apt illustration of Micha’s special social status in Hadassim: “Mushi [Meushara Chayun] was in love with Micha. A teacher once asked her a question, and she just sat frozen and didn’t want to answer. After class, she told me that she was too ashamed of what Micha would think of her answer: ‘What would Micha say?!’

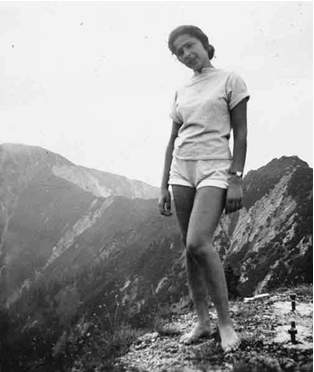

B. The Betrayed Princess

If Micha Spirah was Hadassim’s prince , then Ofra Shapirah was its princess. Rachel and Jeremiah’s beautiful and gifted daughter was an excellent student – she skipped two years of school – and she was the prima ballerina by the time high school came around. Some of my friends claim that the prima ballerina in their elementary school years was Amida Chazanovsky, of blessed memory. One of my journal entries from my first year at the school, in the seventh grade, actually recounts how Amida took it upon herself to teach me how to dance but eventually gave it up, not for want of talent on my part, but because of my overall personality, which was unsuited to the art.

Ofra Shapirah

Among the adult troupe, the title of “Prima Ballerina” seemed to belong to ‘Prince’ Micha Spira’s partner. His first partner was Metuka. But Ofra was in love with Micha, and wanted to be closer to him. She asked Metuka to let go of Micha for her sake, and Metuka eventually gave in, unperturbed by the fact that by doing so she was hurting her prestige and social status. Metuka never cared for such things, not then and not today. I loved her precisely for that reason, and I still love her for it.

According to Micah, Jeremiah and Rachel were very unhappy that her daughter was involved with him, going as far as trying to expel him in order to separate the young couple. Metuka, on the other hand, says that Micha wasn’t satisfied with his youthful romance and tried to enlist other girls in his adventures, hurting Ofra in the process. Still another picture is painted by Drora Aharoni, who recounts that when Rachel was dying of cancer she asked, for her last wish, that Ofra and Micha be married.

Metuka: “When I arrived in Hadassim in 1948, Ofra was in Unit B and I was in Unit A. Though I was older than her, she was already a year ahead of me in school – she was exceptionally gifted. She initially wanted to get close to me because she had a crush on my brother Alex. But we were already good friends by the time she admitted that…

“Ofra taught me all the War of Independence songs; it was very soon that I was transformed into at least a half-sabra, under her guidance. She was the only one I talked to about my Holocaust stories. She treated me like family, giving me the kind of empowerment I needed so badly then.”

Ofra Shapirah

“She was always kind and supportive. I never felt that she had any unique privileges as the directors’ daughter. She was utterly devoid of arrogance; on the contrary, she rebelled against being separated from the rest of the community, always fighting to be with the rest of the children. It frustrated her that she couldn’t reside with the children in her unit, and there were many quarrels between her and her parents on this issue. Jeremiah and Rachel would tell her that she had her own home to live in, that she wasn’t going to be allowed to take the place of another child who might need a bed. We were given new ‘Aliyat Hanoar’ uniforms twice a year, and Ofra was enamored with these – she was absolutely obsessed with trying to get her own set of them. She continually begged Rachel to buy her the same uniforms, so she could be like all the rest of us. I remember being in the Shapirah house and seeing her crying to her mother, her tears coming in bitter waves, pleading with her:

‘Take me to Netanya [the big city] and buy me clothes like these!’ Of course, Ofra never got them. They never went to Netanya, as Rachel never seemed to have time for her own children. In contrast, she was all for giving me some of her own, very fashionable and beautiful dresses -- she was fastidious about caring for the other students, even at the expense of her own children.

“Ofra and I spent many joyous hours in Hadassim dancing together in the years to come. We were best friends in heart and soul. When her brother Rani was born, we used to spend countless hours babysitting. That was when I began to admire their home’s high artistic atmosphere; they had all sorts of breathtaking paintings, statues and other artworks, and the house just radiated character and culture.

“Both of us worked with Philly Alon on arts and crafts, and some of these items used to sell at very high prices in Tel Aviv’s Maskit [a leading Israeli Jewelry firm] exhibition at the end of the year. Our friendship evolved over these years to encompass almost every aspect of life – we worked together, danced together and spent countless hours in her home. She would casually join with me and my family on my home visits in Netanya. My parents lived in Netanya’s Vatikim neighborhood at the time , so Ofra and I would walk there by foot for several hours through the broad fields and citrus groves, crossing the trails to my adopted parents’ apartment. Our connection was cemented during those long and blessed walks.

“We were joined after a while by Tova Shwartz, another Holoc aust survivor, and the three of us quickly became an inseparable trio – that is, until Gila Almagor arrived. I understood from the outset what kind of person Gila was, and determined not to have anything to do with her. I even gave Ofra an ultimatum, forcing her to pick between Gila and me; she begged that I allow her to join our group, so that we would make a quartet where there was once a trio, but I refused. I simply couldn’t take her personality. Unfortunately, this meant the end of a close friendship. We didn’t fall out; we remained friends, but we were never as close as we’d once been.”

Micha: “Ofra was one year ahead of me in school. We met in the dance troupe, where people were grouped by the grades they were in. I’d been interested in Zafr a before joining the troupe. My first girlfriend in Hadassim was actually Yardena, but after that I went through a period when I was torn between two girls I was interested in: Ofra, and Nurit Barmor. There was a while when I was taking one or the other on long walks between the dining hall and the residential area. Ultimately I chose Ofra, and soon I began to fall in love with her.

“Ofra was bright, stunningly beautiful and a brilliant dancer. I remember courting her like a Romeo after his Juliet, waiting on her roof until could spot her across the grounds coming as she came back from class. Then I’d come down to my room to get my accordion, so I could serenade her once our eyes met in front of the dining hall.

“If you want me to define what love meant to me (my language is not romantic, though my eyes and my accordion are), even if love defies definition, I would say that in the tenth grade, it was a total love: we spent every week waiting anxiously for Friday – there was an apple tree that was only for us, our own place, behind the principals’ office, about a hundred feet from her parents’ house. Every Friday night I made Ofra mine under that apple tree, while her father, Jeremiah, walked the grounds and yelled: ‘Ofra! Ofra!’ We could hear him, of course, and we trusted Yoseph, the guard, not to reveal our secret. Yoseph lived in Kfar Neter, and he was the only one who knew about our little hiding place. He used to alert me of Jeremiah’s whereabouts.

“Ofra and I broke all the taboos: we enjoyed a fully sexual relationship starting in tenth grade. So Jeremiah and Rachel had every reason to be concerned: the barbarian was sleeping with their beloved daughter. Fortunately, we were well apprised of the relevant biology, so we were careful not to get her pregnant. And our love was great.

“Our love began to decay by the time Ofra graduated from high school, a year before me. At that point she left to study biochemistry at the Technion in Haifa. We remained friends, though she had other suitors at that point.”

C. Cinderella

“I was also seeing another girl during this period, Shoske Grinberg-Shulman,” Micha continues. “Shoshke was in the class below mine. She was a fascinating girl: her family had moved to Germany, and she had come back to Israel on her own. We had a passionate relationship, but not on the same scale as my relationship with Ofra.”

Gideon: “Shoshke was a wonderful girl. I loved her, and she loved me too, in her own way. We used to go on walks together, but it never reached the level of a relationship. Micha won her attention in the end; he was the prince of the village – I admired him, without a tinge of envy. We were good friends, and he used to help me with my studies. But I’m convinced that if he weren’t in the picture, Shoske would have fallen for me, instead.”

Shoske Grinberg-Shulman

Metuka still feels that Micha really hurt Ofra. “She complained to me at the time that he was betraying her with Shoshke. He really should have picked one or the other -- Ofra or Shoshke – and not dated both simultaneously, and hurting them both. I was very angry at him. ”

Shoshke: “I was Micha’s secret girlfriend. Our love was something special. It started two days after my arrival at Hadassim. I had no idea that he had a girlfriend; I actually liked Ofra – when I first met her, I asked her if she wanted to go see a movie with me in Netanya. Then, when we came back to the village, she went back to her parents’ house while I walked back to my room at the “train” (my roommates’ nickname for our residence), when suddenly Micha jumped out from the train in front of our porch, like Tarzan taming Jane. That’s how it all started, and it continued on for three years.

“Micha was a very attractive boy. He was all charm: a smooth dancer, full of pride and banter. I guess I’m the type to fall head over heals for someone. I found out early on about Ofra, but by that time I was already hovering in the skies and couldn’t step back from my feelings. The romance lasted a long time, for as long as he remained in Hadassim and even afterwards, for a year, while he was in college. It was a powerful love for me in my early years, full of vivid memories, but it was also quite difficult, as I was the ‘other,’ hidden lover. But I wasn’t the only partner in this affair; if a relationship can last for such a long time, it means there was a definite connection there. It was a sign that Micha indeed loved me. It was a really difficult time for me, with lots of ups and downs, so there would have been no way for me to stay in the relationship if the feelings weren’t mutual.

“Still, our love was kept at the platonic level. I’d internalized the taboo about sex from my father in the years he disguised himself as a priest, to avoid being killed in the Holocaust, and from my own education in a Polish convent from an early age. Whenever I was with Micha, I felt as if my father were standing over me and watching everything we were doing. I was taught to repress my sexuality, and it was something I carried with me to Hadassim, where I used to skip Avinoam Kaplan’s sex education class, for his recourse to ‘profanity’. Even as I lay next to Micha in his little cubicle in Yosi Mar- Chaim’s attic, where he stayed during his first year of university, I had my baby doll with me, and the two of us slept next to each other the whole night without doing anything illicit. There was a definite partition separating us.

Micha

“You are the meaning of Dawn,” Micha spoke to her softly as he lay gazing at her face, glowing in her sleep. Micha loved the complex, unresolved tide of arousal he felt in her presence. He lay there, thinking to himself, and held a dialogue with the Shoshke as she could have been without the Holocaust, without the convent and the father who had become priest over her life. In an apartment nearby, Ofra was sleeping alone, dreaming about him, as the moon in her window grew paler in the early morning. Ofra knew that Micha was going to marry her. It was a feeling imprinted in her from the moment they became a couple, when they stood onstage during the 1954 Shavuot performance of Reapers’ Dance.

Back in his cubicle, Micha was listening to a jazz tune on the radio that had been replaying through the night, and he fell back to sleep, his soul full of joy.

Though he was a chemistry and biology student, his heart was still absorbed in dance and music. He was still dancing with Ofra these days, in Dror Ben Dov’s student troupe. He was certain that Dror was fantasizing about Ofra, though he wasn’t sure whether he was actually sleeping with her. He woke up again, and his eyes went back to looking at the deep sun-fire of Shoshke’s face, his left arm still holding up her still-dreaming head. He was thinking that she would never again need to retire to her convent, the convent of a dreamer who never possesses the objects of her desires. When he woke up again afterwards, there was no one next to him on the pillow; Shoshke was gone, and the only thing left for him was a note in her picturesque handwriting:

Trying to imagine your scent…I smell my fingers… I remember how much I love you,

As Moses loved the whispering coals,

Eating them feverishly, so he could stutter

In my heart’s mine, your coals are whispering

I cry like the crying horizon

Touched by the sun, I am your horizon, You are beyond mine. You are a prince and

I am a foundling

The searing force of his dream blazed in his forehead.

He knew, then and there, that Shoshke was lost to him. He had seen something of that dream when he first met her three years before, carrying her suitcase to her new room. He’d heard the moving rhythm of her voice, he had written it down in his mind like a musical dictation. “But I’ve forgotten the code, now,” he thought to himself, as he was drawn from his bed by the shrill birdsong and the sun’s golden embrace outside. His imagination took him back to the ruins on Gordon Street in 1944, on that fateful morning of the year of Normandy. Uri’s composition on the miracle of Normandy flitted somewhere on the edge of his consciousness now, too. He had become a dancer then, on that day in 1944; he was born again, and he would dance forever, to the very end of time.

Micha rose up to dance, and the dance within him expressed itself in the space of his room. He picked up the record on the corner of his desk, near Yosi Mar-Chaim’s clarinet. He saw the name of the composer on the back -- “Scriabin”2. It wasn’t his record, or Chaim’s. “I guess she left it here for me as a souvenir, since she couldn’t have forgotten it,” he thought to himself as he continued his dance steps around the room. The rhythm helped him relax. The inner peace that reigned in his mind was the same ecstatic pull that found him when he first heard Schnabel’s Opus 110 on that night of Tikkun Leil Shavuot – the joyous call of silence. It was in this state that he felt sure, somehow, that he would know the answers for Professor Reich’s biology discussion the next morning – the same professor Reich who treated him as his own son.

Micha, Shoske and Ofra

Micha danced alone in his cubicle on the fifth floor of Mar-Chaim’s house, facing the synagogue in Frumin’s House. He had always used the phone in the pharmacy on the third floor to call Shoshke. “There won’t be any more phone calls,” he told himself.

His body, the perfect instrument of dance, extended in sw ift lines and brilliant curves across the sweep of the room. His inner eye moved as if from the outside and gave him an instantaneous picture of what he looked like from every angle. That was always the hidden image he was searching for. “But what is the mind’s hidden pattern?” he asked himself as he hovered above the floor of his room, looking for the hidden dance within his dance. When he began imagining himself being observed by Shoshke, the acme of beauty occurred -- his body started spinning on its own, and he seemed to forget everything for a moment.

Then the line with which he had risen awake came back to him: The whispering coals’ pleasure, the color of Sun’s dying twenty billion years began to color that morning’s blaze. He fixed his inner vision on that spinning motion, on that unconscious moment when he took flight in his room and hovered in the air, only this time he wanted to replicate it, to reproduce it with conscious fidelity, in order to be able to share it with Gideon later on, to compare it with the disc-throw diagrams in his friend’s sports books. Disc throwing was an art too, after all.

He remembered what had happened to grandpa Schwabe on the Mount of Truth, with Isadora Duncan . Her dance steps had taken flight quickly, as if crossing the sky and roaming the clouds in overwhelming acceleration. She had the same exhilarating height, the elegant sweep toward the unexpected – a silent dialogue between her spirit and her physical position. It looked something like genesis, his grandfather had told him. He told him that she had said that she felt in her dancing as if she were being sculpted by somebody. Schwabe told him that she had described it thus: “I was riding nude on the back of some entity – I don’t remember whether it was a phoenix or a human being – but it was just like Phidias’ moving statues3, as I, along with someone else, both of us naked, merged and molded together with the statue, as one.” Grandpa added that he had heard himself answer her: “All boundaries are actually internal. The one who crosses them borders on heresy – the angels – and at that point you begin to feel the sun as you ride with him on his gigantic carriage, searching for a partner.”

As he finished probing these thoughts, Micha realized it was time to listen to the new record. He stood there and listened to Scriabin’s Prometheus: The Poem of Fire”4. His body performed his mind’s reflected gleams of sound, and did it unconsciously, until the ember of a cry in his throat woke him. It whispered to him, “I remember not wanting to separate from you, how I leapt into the stream of your mouth, onto your tongue; how you pleased me, how you radiated in my whole body and enjoyed me.” As he heard these words, he lost himself in the ecstatic layers of the most beautiful music; he forgot himself in the lunatic harmony, the vision of untethered and defiant motion, which felt like it was going to burst out of him, as if he were giving birth.

Micha was an individualist who did everything his own way. Shoshke, w ith her mesmerizing beauty, was like a Polish love tonic: a taste of a deep emotional melancholy, forged with sharp, creative and intelligent wit, to complement his high nobility. He and Gideon used to listen to her play Chopin’s opus 52 ballade from an adjacent room. She played for him the same way she loved him, fighting against the angel of death riding on her shoulders5, oblivious to the chance that her playing was taking her past the limit, beyond the earth, bringing back her worst terrors of childhood. Her playing brought back the memory of her mother and brother being taken from her, when she was only three years old. She was left to wait for them at their usual meeting place, unaware that t hey were already among the dead. Her father had to disguise himself as a priest and left her in a convent. The imprint of such things on her young mind could only come through in her playing, in the outpouring of what would otherwise have been unbearable for her to hear; it was her only way of expressing loss.6

Micha was a lover of change and challenge. He was truly noble, a man fully empowered with the art of the “flow”. The love triangle of Ofra, Micha and Shoshke was similar to the one in the ancient tale of Tristan and Isolde 7, to which the composer Richard Wagner8gave a musical expression. Just as our western music is founded on the harmonic language of tension (dissonance) and resolution (consonance), the forbidden love of Tristan and Isolde is ennobled by its non-realization, and the longing of protracted arousal that results is conveyed by Wagner in musical terms, through protracted harmonic tension. And just as musical language can be used as a metaphor for a certain conceptual-cultural-ethical phenomena, the love triangle of Ofra-Micha-Shoshke was expressive of a language of love, one of unrest and non-resolution, a language that evoked the spiritual tensions that arose from the Western, Christian9, Modern10 and Jewish-Israeli cultural crisis.

Both women were transitory muses in Micha’s life. In the tenth grade, Ofra was his sun – but she lost her light, eventually. She became the lesser light, as Shoshke became his greater sun. Both of them reflected his unique characteristics, the singular nobility that shone through in his dancing, his epistemological and esthetic sensibility and self- awareness. It is a nobility expressed in a relentless creative-scientific individualism – his own solution to the modern cultural dissonance which he is made to inhabit.

The terror of death, Shoshke’s Holocaust dissonance, is conveyed in her language of love11, and is confronted with a struggle of creative resolution, a resolution which we brought into dialogue with Micha’s creativity. Ofra’s dissonance is her lack of self, her altruism, which resulted from her abandonment by altruistic parents who couldn’t respond to her authentic needs. The seeming resolution of this for her has been her successful scientific career, but that’s only on the surface. In truth, she was betrayed by her husband, just as she was by her parents.

Shoshke’s sun declined, too. When she finally succeeded in cutting the Gordian knot with Micha, she was only able to meet him once in Jerusalem, and this short encounter was a torture for her. While he had already divorced Ofra, she was already married to someone else. Her marriage to Professor Schulman, the famous plastic surgeon she forced on herself for the sake of a static, frozen bond of marriage, was a bond which formed the basis for a second love triangle, when she tried to join another lover to it. But this second triangle could not but disintegrate, since Shoshke wouldn’t endure the tension of a double life. She divorced – and left her lover -- moving on to the third chapter in her life, as a renowned lawyer’s mistress. With his death came the fourth chapter, in which her power to love is manifested solely in grief. Shoske and Ofra fall short of nobility, after all; they’ve never crystallized into their full selves, as they’ve always been dependent on their relationships with others.

Shoshke never saw Micha again after leaving him that note on his pillow. She describes how she was finally rescued from the tempest of her love for him: “The love was overwhelming, but the agony of having to keep it secret was too much. There was too much pain and sorrow, too many ups and downs. But it took my good friend, Sara Hubner, who saw my slow torture, to bring me the pen and paper and force me to end the relationship. ‘Write him a letter and tell him that it’s finished,’ she said.”

Consequently, the person who evokes the connotation of traumatic threat will be chosen as the love object.

Shoshke had tried to solve her dynamic, chaotic relationship with Micha (so dynamic that it became static – like Wagner’s endless chromaticism in “Tristan and Isolde”) by resorting to an overly static marriage to a well-established gentleman, whose unwavering careerism wouldn’t leave room for the dynamic intimate element.

“When Micha got a divorce I was already married. I even married before he did, apparently. I’d had three children with my husband, Dr. Schulman, the busiest plastic surgeon in the country. It was a good marriage, though he was a work machine.”

Shoshke went back to the other extreme, the forbidden love, as a resolution to her frigid, static marriage. She soon fell in love with another man, a different man entirely. “One day a young man came for a visit, and he began courting me immediately. I fell in love with him the very same morning – I fell for a married man. The affair lasted for four years, and it was wonderful. He used to lament that if we were younger we could divorce our spouses and be free for each other. In reality, however, our affair didn’t stop him from having two children with his wife.”

Again the static pattern reveals itself in a seeming dynamic resolution. Shoshke ultimately looked for a genuine resolution in divorce. “After four years of marriage, I left the house. I couldn’t stand the double life. I left when my children were nineteen, seventeen and twelve. The eldest was already in the army while the second was about to enlist, and the twelve year old girl I left with her father. I left the marriage – but the affair didn’t end. Later they kept telling me that I was naïve, that a divorced woman is a threat to the man. But I’m not a threat - I am simply a woman who loves.”

But as a lonely woman in love with an unavailable man, she’d lost the static element she needed. She had once again been thrown into a state of extreme irresolution, of Wagnerian turbulence.

“I had to leave my lover, just as I’d had to leave my husband. It was a painful surgery, without any anesthetic, since I’d loved him deeply but had no way of escaping the hell. Our meetings were never planned, never committed. At least a mistress has something of a predictable schedule to lean on, which tends towards some feeling of security and legitimacy. Wealthy, established men in Rome and in the Middle Ages kept concubines; it was a convention, an institution of sorts. But that’s not what I had at all; I was always asking, ‘when will we meet again?’ and he always answered: ‘I don’t know.’”

With that, she entered another chapter, where her static and dynamic elements were brought into better balance – with a serious, committed lover. It would last her for twelve years.

“Sixteen years ago I met someone – a lawyer who was handling my father’s will. He was stable, prestigious and conservative, though he was married and had children. A romantic relationship evolved between us, lasting for many years.”

But this happier chapter of her life ended tragically, with her lover’s sudden death due to heart failure. What ensued, in her next and current phase, was the idealization of that love, a devotion wedded to something unique and irreplaceable, a resolution anchored in grief. “He died of cardiac arrest four and a half years ago, and I haven’t really lived since that time. It was a once in a lifetime kind of love, and I never really accepted the fact that he’s gone. I’ve tried to let go – I’ve read and done research on this kind of emotional phenomenon. But I can’t keep from mourning him; the man was simply too immense a value in my life. It’s hard to live life on low voltage. When I let myself experience the pain, though, it gets to be too much. It drives me into the wall. And more: unlike his family, I can’t grieve for him publicly.”

“I don’t go to movies, or have any happy thoughts. But I might be ready for new journey, of a different kind. I read an article recently that made a deep impression on me, and I’ve read books that lead me to think there’s another road waiting for me. Judith York wrote about life as a process of necessary losses, and necessary submission. She tells of a man who lost his beloved but eventually met another woman; after they went to bed for the first time and he woke up and saw her at his bedside, he went into shock at first. But that shock eventually gave in to love. So things happen, usually in an unplanned way. So I try not to plan anything. I’ve already experienced the matters of the heart; I’ve already had those things that can only happen once in a lifetime.”

D. Requiem

Ofra and Micha’s marriage didn’t go well; it was a static step that went against the dynamic flow that had characterized their long relationship in Hadassim. That the fire of their love had exhausted itself long before their marriage led to mutual betrayals and affairs. Ofra had already met Yaakov Aloni, her partner in life for thirty-seven years, until her death – even before her marriage to Micha. According to Aloni, Ofra sent him a note on the day she married Micha: “You are the love of my life. I want you for the rest of my life.”

Micha: “After the Six Day War, I commanded a reserve engineering unit in charge of clearing minefields. One day I came back home without telling anyone in advance, only Ofra wasn’t home. When I asked some friends about her whereabouts, I found out she was with Aloni.”

“Why didn’t you two have any children?”

“I wanted to have children, very much so – but she didn’t. She probably had an affair with Ehud Manor [Israel’s m ost prolific and beloved songwriter, an Israel Prize recipient] in addition to her liaison with Aloni. Perhaps she was harboring thoughts of divorce… At any rate, after getting my doctorate I went for a post-doc in New York, at the Albert Einstein Hospital. Ofra came with me, but she went back to Israel at a certain point. That’s when I first thought of divorce myself.

“I was invited back to Israel for a scientific conference. While I was there, we spent two days in a Kibbutz near the Kineret, and we managed to resolve all our issues on friendly terms. The decision of divorce was mutual.”

Aloni: “Ofra was my princess, my great love. I left my first wife so I could be with her. It’s not an exaggeration to say that she was perfect – she was. Our love blinded us completely, but I still say that she was flawless: a perfect woman, perfectly beautiful, and a brilliant student. She was the youngest of her class to receive a PhD – she was twenty- four. She pursued a direction of research that was revolutionary, taking a post in an experimental cancer research department under Professor Gross, where she worked on the thyroid gland. She checked the quantity of hormones T3 and T4 among children. A baby who doesn’t have enough of these hormones needs to receive supplements, or else he becomes mentally handicapped. She developed tests that produce results immediately, helping to save millions of babies all over the world as a result. Her skill was of the kind that allowed her to diagnose a singer with a swollen thyroid -- during a concert.”

“Ofra was engaged in her research work for twenty years. There were various administrational difficulties following the death of Professor Gross, and she was eventually enlisted as an advisor for the national research foundation, where she was promoted to director-general within two years. She used her new position to change the evaluation system for research proposals and grants, helping to cut the middleman between financing and scientists badly in need of grants. Previously, the universities had made it a custom to keep a great deal of this money for themselves, as overhead money. A year after her death, the European Union called with the intention of offering her the directorship of their new foundation for scientific research.

“Apart from her scientific work, she kept up her dancing and devotion to folklore education, as these were her pursuits going all the way back to the “Hora” days. She founded a Hora troupe and a dancing community for small children, focusing particularly on poor neighborhoods, for which she received numerous honors.

“When I decided to study Philosophy and Art History, Ofra was determined to join me. Both of us entered a master’s program in Art History together. Her specialization ended up being in the Middle Ages, so we traveled to Spain in search of medieval manuscripts. “These years of joint study were the happiest in our wonderful thirty-seven years together. Early on we formed a rule, and we always stayed faithful to it: we never went to sleep un-embraced. There was never any tension or conflict between us that wasn’t resolved the very same day. We raised our two daughters together, surrounded in love.”

E. Success or Truth

Yigal Drori, today a professor of History, joined the Hadassim village in 1951 . “Hadassim was viewed as the Israeli Eaton at the time,” he remembers. “It had the same prestige – a boarding school with superior quality and tending toward the development of the independence of students.”

His father, Moshe Drori, had been a senior Shin Bet agent sent to work behind the iron curtain for two years. He worked at the Israeli embassy in Bucharest, aiding and encouraging Jewish emigration. It was customary at the time to have children of embassy workers study in Israeli or Swiss boarding schools.

Yigal: “My father first took me to see the village of Ben Shemen, but I didn’t like it. But when we went to see Hadassim I was hooked. I ended up spending the best years of my life there. I remember many deep intellectual conversations with Shevach Weiss and Zeev Alon. It was those types of mental engagements, in our clubrooms and on the grass, that helped develop my intellectual independence. Shevach was only four years older than us, and he was still in high school at the time. Being around him taugh t me not to treat any issue superficially. It was 1953, the ‘Year of Herzl’ for Israel’s schools, and I won first prize in a state-wide writing contest on the great founder of Zionism. The prize was a flight to Eilat. When I landed there, however, there wasn’t anyone there to greet me or pick me up. I just waited in the airport for a flight back.

“When my father came back from his mission, I moved back home and studied at the Ironi Dalet High school in Tel Avi v. I was an instructor for the United Movement and went on to serve with Nahal [“The Pioneer Youth Forces”], which allowed me to join the Kibbutz Ramat David. But the three ye ars I spent in Hadassim touched on the whole course of everything I managed to achieve later on.”

“What did you think about me in Hadassim?”

“You joined us, Uri, in the seventh grade. The fact that you were a grandnephew of the poet Rachel made a huge impression at the time. You were very sharp and highly intellectual but also aggressive – verbally aggressive, of course. I didn’t like that then, and I also have my reservations about your current publications.”

“Can you give me an example of some work of mine that you don’t like?”

“In principle, there’s no way for a man to be completely objective. A Ukrainian, for example, would describe Khmelnitsky differently than would a Jew. To Ukrainians he’s a national hero, while for Jews he’s an anti-Semite and a murderer. But what disturbs me about your work is the lack of factual support.

“The journalist Uri Avneri once wen t after a public figure, publishing an article in his newspaper, Haolam Haze, to the effect that the man’s sons hadn’t served in the military. What he omitted to mention was that his sons’ ages were five and twelve.

“You did something similar when you wrote about the Lamed Hei and their fall during the War of Independence. You wrote that Yoseph Tabenkin, the battalion commander, was eighty meters from the Lamed Hei but did not offer help. That much is true. But: he was on the other side of the ridge, committed to that operation; he was on another line of communication entirely, so he couldn’t do anything about the Lamed Hei. So we can’t blame him for not offering help, because it wasn’t possible – he didn’t know their situation. Nobody knew it.”

Uri: “Yigal, my friend, the example you brought is excellent, but it only refutes the claim against me. Here are the refutations: Yoseph Tabenkin was commander for the Palmach fourth battalion, and the Lamed Hei was a combined unit of the sixth and the Moriyah battalions. They were sent on their mission by Tzvi Zamir, the sixth battalion’s commander.

“At the time of the Lamed Hei affair, Tabenkin was in Tel Aviv -- not in the Gush Etzion region. It’s true that he was guilty of not offering help, but that was in the context of another affair – the Chulda Convoy affair, in March 1948. The Lamed Hei affair happened in January.

“The Chulda area was completely flat. There wasn’t any natural cover, and there was only one communication network. Tabenkin wasn’t 800 meters away from them – he was 300 meters away. If a high school student were to make the kind of mistake you just did, he’d be given a grade of ‘unsatisfactory’. But you’re an historian of the Jewish settlement. If you can make a mistake of that order, if you can make that many misstatements regarding a single event that you’ve surely covered in your courses at Tel Aviv University, the Open University and the high school you directed, it says something about these institutions’ level. All I can gather from what you’ve said is that you’ve read nothing of what I wrote, though you’ve certainly been privy to gossip about my work from people who have no interest in the truth and use academics like you to obscure reality.”

“Uri, as usual you show your aggressive style and propensity for exaggeration!”

“The validity of my claims is the only thing that interests me. Intellectual weaklings find refuge in style. You can talk about my style all you want with others, not with me. I just want to ask you why you base you claim about me on an unfounded example. It leads me to assume that you’ve done this before, when I wasn’t there to rebut – and that people may have taken you seriously precisely because you’re a historian in this field. This is how Israeli culture declines. This is why we don’t learn the right lessons, and the state functions worse and worse every year.”

“As usual, you keep making generalizations. Uri, if your style were less aggressive you might have attained a little more success...”

“I’m interested in the truth, not success.”

F. An Aria from Samson and Delilah

Nurit Barmor–Azulai came into our world in Hadassim in the ninth grade, apparently all the way down from the great big world of international affairs. Her father, Yaakov Barmor, was ostensibly the first secretary at Israeli embassy in Warsaw. In fact, he was a Shin Bet representative. Nurit had spent her time in Europe until she joined us in the village.

Nurit: “In 1950, my father joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and we were sent to Warsaw. I was educated in American schools there until the eighth grade, when I had to decide between attending a Swiss boarding school or enrolling in another American school in a military base in Berlin – the other alternative was going to an Israeli boarding school. There were other children of ambassadors in Hadassim at the time, and I decided to go there, too. I’d visited there and liked it. When I traveled back to Warsaw with my parents during the summer break, we stopped in Italy. Father showed me the Tiber River in Rome and went on about how beautiful it was. I looked at him like he was crazy. ‘How can you forget our Yarkon [the larger coastal river in “Israel]?’ I asked him.

The Yarkon River is an unshakable part of my identity. I resented my father’s exuberant praise of the Tiber.

Nurit Barmor–Azulai

“Then we saw what postwar Europe was like.

The houses in 1954 were the blackest of all black. Everything just seemed depressing to me. The Italy trip really opened my eyes to just how new and positive Israel was in contrast to all this European shabbiness. Eve rything was alien and oppressive. When I got to Milan – my father’s cousin lived there – I asked my father to buy tickets at La Scala, the famous opera house. It was a great dream of mine to visit there. I saw ‘Tosca’. It was as if I’d waited for this experience all my life. Our train stopped at Warsaw on my fourteenth birthday; I’d already celebrated i t a day earlier in Prague, but the atmosphere there was equally bleak: Ash-grey Gothic buildings, dark and depressing. Europe had been slain by war; everywhere the stores were closed down, wood covering the entrances. It was depressing just to walk in the streets, so I celebrated my birthday in Bohemia’s forests.

Warsaw, on the other hand, was an island of comfort in a communist country. Life was clearly different there. When we were going back to our apartment, father asked the cab driver to pass through the Franchiskanska-Nlevsky corner. He was trying to locate what was left of his house before the war. But when we got there the whole area was fenced in, and there were only heaps of bricks where his house had been. My father just fell on the ground, crying his heart out.

“The embassy people all lived across the river. There were houses being built there after the war ended, with individual rooms for each family member, and that’s where my parents moved. All of a sudden we had all this abundance; we had a housekeeper, and I used to lay by the fireplace or sit at the window sill reading books. We bought a record player and some records, and we started going to concerts all the time. I spent four months there, returning to Hadassim after the holiday.”

Yaakov and Sara, Nurit’s parents, both immigrated to Israel from Poland before the war. They met and married in their new homeland, where they moved into the Neve Shaanan neighborhood in Tel Aviv’s poor southern side. Yaakov served with the British Mandate police force, but given his later career it’s a reasonable assumption that he was also spying for the Hagana’s Shin Bet. He was already a member of Mapai and the Histadrut. Most of his relatives were Beitar people, so his family gatherings were predictably filled with ideological tension.

Nurit was born in 1940, and her brother, Shlomi, followed her into the world five years later. When she reached the tender age of six, her father grew unsatisfied with her neighborhood Bialik school and started sending her to the more elite Balfour school in the afternoons. There was a material gap between her and the other students there, but not a cultural one. Still, Yaakov was so meticulous about her education that he tutored her in English, tested her spelling and even assigned her quizzes on a great variety of subjects.

Nurit’s love for music had begun at an early age. By the age of seven she was standing at the window of their apartment and singing an aria from “Samson and Delilah,” hoping that someone might hear her and help pay for her music lessons. With the establishment of the state, Yaakov rose to a senior position at the Histadrut health office, whereupon the family moved to the Histadrut health fund workers’ apartment complex in Tel Aviv’s prosperous northern quarter. She transferred from the Balfour school to the Beit Chinuch School in North Tel Aviv. When she graduated from elementary school, Yaakov joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, while she was sent to Hadassim.

“I hated it at the beginning, and actually wanted to escape. But soon enough Chilli developed a crush on me, and with his help I was given access to the high society of the children’s community and met Yardena, Gideon Ariel, Avi Meiri, Iris, Esther Korkidi, and Danni Nachamias. Life in Hadassim quickly became something wonderful.

“I didn’t really have much contact with you, Uri. You were a lone wolf, a philosopher, and you tended to be confrontational. I remember how you once wrote a poem about two train wagons that never meet; you strode into our room and handed it to us.

I loved Micha. We used to spend countless hours flirting with each other. Hadassim gave me a home but without the stress, without the all the exaggerated academic pressure. My best friend was Esther Korkidi. She once told me that ‘I know that there’s goodness in life, because I can see it in yours, even if not in mine.’”

1 It’s not clear what caused the explosion. Michael believes it might have been bombardment from Italian planes.

2 Alexander Scriabin (1872- 1915) A Russian composer whose work was primarily modern, weaving together his expressive musical vision with his mystical philosophy. His style tended to mediate between the Romantic and the modern, as it was his musical generation that had to reconcile the two eras.

3 The greatest of the ancient Greek sculptors, who according to the legend was able to animate his sculptures.

4 The last symphony Scriabin wrote, consisting of a single movement. Prometheus had given the fire of heaven to mankind, and a struggle ensued between good and evil which culminated in a victory of the creative will in the merging of the human with the divine.

5 “Why should we fear death, and his angel rides on our shoulders, and his bit is in our lips; and with a resurrection’s blast/cheer on our lips and playful neighing we will hop towards our graves” Chaim Nachman Bialik, “Davar” .

6 She was already expecting to lose her relationship with Micha at this point.

7 The theme of the legend of “Tristan and Isolde” is all- embracing love, which is hopeless in this world, and the consummation of which is only attainable in death. Wagner used surprising harmonies to portray this, musical devices that pointed toward the later work of Arnold Schoenberg and his pupil, Alban Berg.

8 Richard Wagner’s musical style (1813-1883) is generally considered the peak of the Romantic period, due to its unprecedented emotional focus. His new forms of harmonic chromaticism, as explored in “Tristan and Isolde,” prepared the way for 20 th century atonality.

9 This is the elemental pattern of sexual passion in the West – a longing for someone outside the marriage. Natural, earthly happiness meant everything to people in the ancient period, before “this world” was set against the “the next world” and Man was split into “body” and “soul”. The pagan conception of living according to nature is the idea against which the West’s ancestors rebelled. Plato rebelled against it when he determined that this world is only an obscure and deteriorated reflection of the perfect world of forms; the Gnostics rebelled against it when they determined that an evil god, a demiurge created our world and our loathsome bodies, and that the soul’s role is to ascend from the body’s imprisonment, from the exile on earth and to return to its source in the true god’s bosom; Christianity rebelled against it ,when it turned life to death and death (“Heaven’s Kingdom”) to the longed-for life at the end of the corridor. It was in Athens, in Nazareth, in the secretive caves in Iran and in Yehuda desert that Western culture became a culture of longing.

10 The eruption of Modernism (1910-1930) on the eve of WWI, caused breaches in the social order – something that could be observed in the Russian revolution of 1905, the accelerating propaganda of “radical” parties and a great quantity of art works which radically simplified or completely rejected the existing custom. In 1913, Igor Stravinsky, working with Sergei Diaghilev and the Russian Ballet, composed the “The Rite of Spring,” a work that depicted human sacrifice. Young painters like Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse had begun shaking the art world with their new constructions. This development gave new meaning to the concept “Modernism”. Its nucleus was the adoption of disintegration and disturbance. In the 19 th century artists still tended to believe in “progress.” With the rise of Modernism, however, the artist was reformed as a revolutionary, as a destroyer and not a teacher.

11 Shoshke had to endure a sequence of losses as a Holocaust child, and it constituted a trauma that led to an “other woman” syndrome as her only map of intimacy. When added to the Western dualistic conception of love, the abandonment of the child by his first sources of intimacy will tend to harm their bonding ability and their trust in the object of intimacy. Thus, such a child might develop a defense mechanism of splitting from their later sources of intimacy, and disassociating the objects on which they project the need for safety and trust from the object on which they project the need for romantic love.