Book.

The Discus Thrower and his Dream Factory

Chapter 7. Love and Work

The doctoral program curriculum was similar to the one I had pursued for the Master’s degree. There were academic requirements within and outside the focus of the individual’s interest and there was a mandatory research project. I registered for Fall classes in statistics and several new courses were available which sounded intriguing. One was “Cellular Physiology” with a new professor, Dr. Eddigton and the course description described how the students would become proficient with the electron microscope. I was completely shocked to learn that in the one short year that I had been away that the University had acquired such a sophisticated tool for the study of human movement. Another new course which set my heart ablaze was “Biomechanics of Performance” to be taught by Dr. Stanley Plagenhoef. He was also a new professor and the class had a promising title. I eagerly anticipated the Biomechanics class since it sounded more promising to my way of thinking than even Kinesiology had. I had my fingers crossed when I went into the first class.

When I stepped into the class room for the first day, I was in for another surprise. There was my nemesis from before. The tough pretty girl, who had stood up to me after statistics and slammed the door in my face outside of Dr. Kroll lab, was sitting in the front row. I considered my options. Then, selecting bravery over cowardice, I sat down next to her.

I reminded her who I was and she told me her name was Ann Penny. At this point, she explained that she was half way through the Master’s program and then would continue towards the doctorate. Following graduation from the University of North Carolina, she had taught physical education in a private school in Princeton, New Jersey for two years. Suddenly, the lights flashed in my brain! Now I understood why I had not met her during my Master’s program. As we chatted before the professor arrived to start the class, I learned of her disinclination to teach children in elementary or high school. Apparently it had taken less than one full day of teaching for her to realize that she had made a huge mistake in her college career path. Now she was in graduate school at the University of Massachusetts with the goal of following a more scientific program of study.

We were soon joined by Jim Salitas, a friend that I had first met during my Master’s program. It transpired that Jim and Ann had become very close friends during the previous year. They had studied together in several classes and shared many discussions over coffee. At that time there were few women in this field of study so, as it turned out, Ann was the only girl in class. Fortunately for her, she was intelligent, direct, and capable. Jim sat down and we began discussing our class schedules, what we had done during the summer, and people that at least two of us happened to know. It was one of those conversations where everyone was talking at the same time but somehow all was understood.

We also caught up on the details of our private lives. Jim was originally from New Hampshire and was married with two children. His wife was a wonderful person who supported Jim completely in his academic quest. But they struggled financially since she could only work as a babysitter and his assistantship was too small to support a family of four. I reminded Jim of how he had helped me during my Master’s program to overcome my all-thumbs approach to loading the movie projector. We had laughed until tears poured as I tried to thread the film through the maze of pressure plates and make the “loops” form properly. Now we were able to share those hilarious moments again. Once again, my old characteristic of persistence and effort rescued me. I never, never, never give up when I undertake a task. Sometimes it takes extra time and effort, but I never quit and eventually I was able to operate the projector. Jim agreed with my description of the times and my personality assessment.

Over endless cups of coffee, Jim and I learned more about Ann. She was born in Raleigh, North Carolina but spent most of her childhood in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. “Go Heels” was a phrase we heard often but to an Israeli, this made no sense and to a New England Yankee like Jim this was nearly a declaration of war. In addition, we were informed that the sky was Carolina blue because God was a Tarheel. In spite of this seeming craziness, it turned out that Ann too was obsessed with understanding the anatomy and the mechanisms of controlling the human body. I was more intrigued by the mechanical aspects, while Ann was more interested in the nervous system’s impact on the functions of movement. Jim’s plans were to find a teaching position in a college in New England since this was close to home for both Jim and his wife.

Our friendship flourished and soon we were the “Three Musketeers”. Jim, Ann and I would meet in class, in the laboratories, and over coffee. Frequently, we drove to the local ice cream shop where Jim and I would consume enormous hamburgers, milkshakes, followed by four-scope banana splits. Ann would drink her coffee and shake her head at the amount of food two men could eat and remain trim. Our shared common interests seemed endless and were lucky enough to be able to help each other with difficult class work. If one of us could not solve a problem, eventually we would collectively discover the answer.

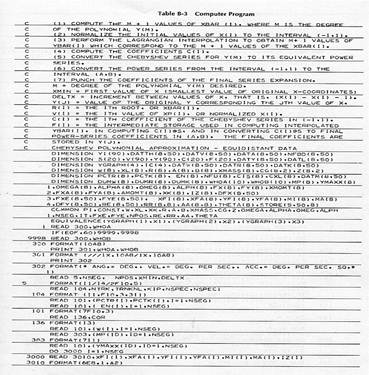

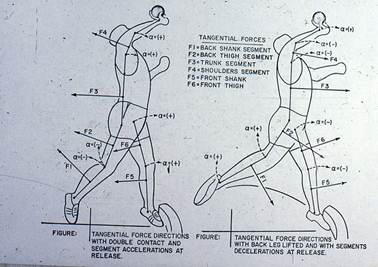

As the semester progressed, I became convinced that biomechanics provided the way for me to understand and produce answers to my many questions about movements and activities. Clearly, biomechanics was my field and gave me a focus to achieve the answers I sought. But there were new aspects which intrigued me continually. Our biomechanics professor, Dr. Plagenhoef, had developed a computer program written in FORTRAN early in his career.

Section of one of the first ever program for Biomechanics

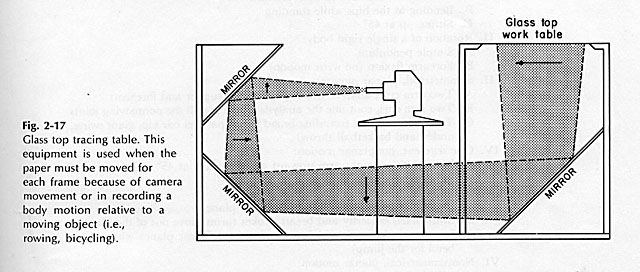

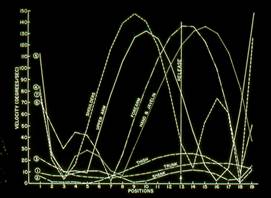

Unfortunately, the process for the biomechanical analysis was excessively tedious. The process required projecting a 16mm film of the movement one individual frame at a time. The film sequence was projected through a series of angled mirrors onto a glass-topped table. As each frame appeared, the location of the body’s joints was “traced” by marking points on a large piece of paper which had been taped onto the glass top. This process was known as “digitizing”. The next step required measuring the various angles and distances, carefully recording them in a table, and sitting for hours in the computer center to punch the numbers onto computer cards. These computer punched cards were then submitted to the computer center for processing by the biomechanical program. If all of the point information had been correctly transmitted to the computer punch cards, a long, thick stack of paper was the happy result. But if even one card were wrong, upside down, or missing, there was only a thin computer print-out of failure. I am sorry to say that there were many times that after hours of waiting, the result was disappointment. However, if all had gone according to plan, the program could correctly calculate the kinematic characteristic of moving bodies.

Projection system for tracing films, frame by frame

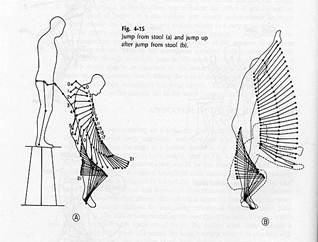

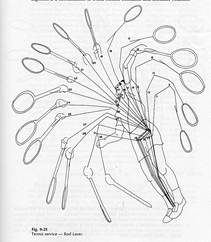

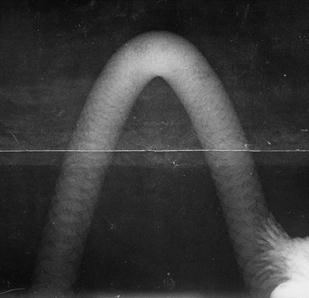

The kinematic parameters which the program produced were the positions, velocities and accelerations of each of the selected joints. The information for any one of these joints and for any of the selected kinematic parameters could be plotted on paper. The plotted data yielded diagrams such as the following examples of stepping from a table, jumping into the air, and hitting a tennis serve.

Composite tracing

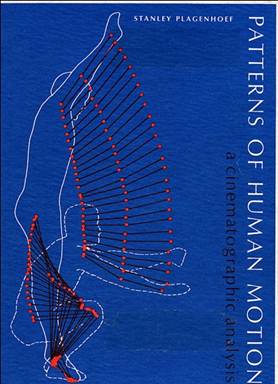

During the semesters that Dr. Plagenhoef taught our class, he was in the process of writing a book: “Pattern of Human Motion.” All of the biomechanics class members, including Ann and me, contributed most of the figures to his book. The tables and diagrams were ours as well although no royalties resulted from our work. We were typical graduate school slaves but the learning and experience more than made up for any financial rewards or lack thereof. After all, the students were there to learn not to earn a living.

Dr. Plagenhoef’s book written in our biomechanics class

That was my first introduction to using a computer to measure or quantify human movement. I became obsessed with using this tracing procedure and Dr. Plagenhoef’s biomechanical program. I wanted to analyze as many Track and Field events as possible with this technique. At that time, I was the assistant track coach and shared an office with the head coach, Ken O’Brien. This was the same coach who had invited me to work with the Field events during the year that I pursued my Master’s degree. He had enthusiastically welcomed me back after my stint in Indiana and Ohio and given me the job of working with the Field athletes as I had previously.

I discovered that Ken had acquired some fantastic “loop” films for each skill that was needed in Track and Field events. For example, one film showed a javelin thrower running down the runway, employing the complicated cross step running approach pattern, planting the front leg, and throwing the javelin. Since the most important part of this technique for my biomechanical analysis was from the moment of the foot plant until the release of the javelin, I cut that section out of the “loop” for analysis. After I cut that section out, I reconnected the remaining film into a “loop”. Now, if someone watched the film of the javelin throw, the athlete ran down the runway with the complicated crossover footwork followed by the javelin flying in the air. Everything in between the run and the javelin flight was missing. The same omissions occurred for the takeoff in the high jump, the release of the discus, the step and stretch over the hurdle, and all of the other films that Ken had purchased to teach Track and Field events. Of course, I had planned to return these sections to their proper places in the “loop” but before that happened, the losses were discovered.

One afternoon, Ann was working on some of her studies sitting at my desk in the office I shared with Ken O’Brien. Suddenly, Ken burst into the office. He slammed his books down on his desk and began pulling open each of the metal file cabinet drawers all the while shouting about films. He would yank out a metal drawer, rummage about in the files, throw things up into the air, and then slam the drawer back into place. All of this time, he maintained a thunderous monologue about missing films and shouted about Gideon cutting the movies. This was so completely out of character for the normally mild and gentle Ken O’Brien that Ann oozed under the desk in hopes that she would go unnoticed. After a few minutes of this tirade, Ken breathlessly sat down in his desk chair and noticed Ann who by then was peaking warily from behind the desk. Despite his enormous frustration, Ken smiled sheepishly and suggested that she warn me of my fate if the films were not repaired quickly to their proper sequences. If you can image a slap-stick comedy act with drawers flying and the ravings of a mad man while an innocent bystander hides watching in fear, you have a glimpse of what that day looked like. Needless to say, I returned the missing film sections as quickly as possible.

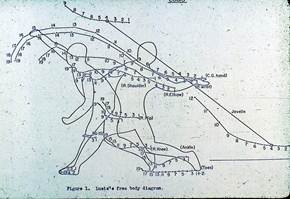

In my own defense, I spent long hours analyzing these athletic movement sequences which had been temporarily removed from the film. One of my first studies was to examine the style and technique of the current world record holder in the javelin throw. The athlete was Janis Lusis, a Latvian and Soviet athlete, who won a bronze medal at the Tokyo Olympics, a gold medal in the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, and a silver medal in Munich in 1972. His performances were amazing and it was a tremendous accomplishment to perform at such an elevated level across three Olympiads.

Janis Lusis breaking the World Record

I wanted to understand his technique from a quantifiable rather than merely visual perspective. I traced the film, frame by frame, measured the coordinates, punched the computer cards, and ran the biomechanical program on the University’s main frame computer. The results were fascinating and I immediately began work on a presentation for the International Track and Field Coaches convention and for publication in the Track and Field Quarterly Review.

In both my presentation and the publication about Lusis’ javelin throw there were diagrams of the movement path followed by each joint. In addition, I demonstrated how the athlete was able to coordinate the acceleration and deceleration of the various segments. I explained quantitatively that the lower, heavier parts of the body, such as the legs and torso, had to rapidly slow down close to the release of the javelin thus transferring the momentum to the arms and javelin. The analogy I employed was of a speeding car crashing into a wall and sending the driver flying through the windshield. My speech and this article described many details about how Lusis performed and how his style could be utilized by other athletes.

Lusis tracing and the velocities output results

I was very optimistic about the usefulness of biomechanical techniques in understanding the activities in which many of these people had spent their entire working careers. My experiences, until then, were that some coaches were as stubborn as donkeys and resistant to change. Their attitude was that if it had not been done before, there was no reason to do it now. Because I was aware of this attitude, I was somewhat apprehensive prior to my presentation and the response that it might receive. I just took a deep breath and decided to try my best to explain the beauty and usefulness of biomechanical analyses to these coaches. Then, let the chips fall where they may, as the saying goes.

I was pleased and felt justified after my talk when many of the coaches attending my presentation at the convention were enthusiastic about this new biomechanical information. Anything that could help their athletes perform better and make them better coaches was welcome. This was a refreshing attitude and one that I hoped to spread throughout the coaching community.

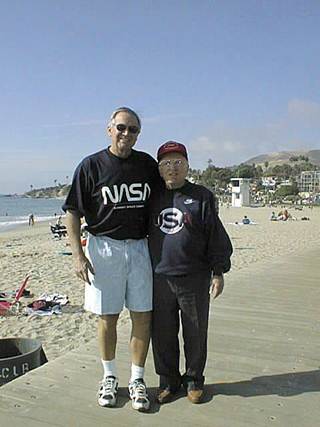

The editor of the Track and Field Quarterly Review, George Dales, was extremely enthusiastic about the potential of biomechanical analyses had for athletes. It was at this convention that I met George in person was the first time, since previously, we had only communicated by mail. George was the head coach at the University of Western Michigan in Kalamazoo and was obsessed with Track and Field from both the athletes and coaches perspective. He wanted to help this population in meaningful ways and sought to publish articles that would accomplish this goal. George enthusiastically embraced my method of performance analysis and has published many of my research papers throughout the 40 years since that first article. He has been a great supporter and friend of mine and Ann’s and we cherish his friendship.

Forty years of professional and personal friendship with George Dales

I returned to Amherst after the convention elated by the response I and the material I had presented had been received. Now it was back to work on publications, academic class studies, teaching, and coaching. In the back of my mind, however, I pondered what would serve as a good Ph.D. dissertation topic. The thinking process was similar to my dilemma earlier. How could I combine the mechanical part of movement with the physiological portion? I knew that Dr. Ricci, my dissertation advisor, would want a concentration in the physiological part but that had less appeal to me so I needed a subject that would interest both of us. I reflected on my discus and shot putting background from the perspective of the new Olympic attitudes concerning supplements and performance enhancing substances. I had attended a few conferences dealing with the Olympians as well as chatted with athletes throughout the Yankee Conference during track meets when I coached the Field events. It became increasing apparent that pharmaceuticals were becoming as much a part of sports as training and equipment were. All of the college athletes I met were absolutely convinced that “the other guy” was taking drugs, such as anabolic steroids, to enhance their performances.

There was a growing controversy whether anabolic steroids actually produced enhanced musculature and, therefore, improved performances or was there only a placebo effect. I had heard from my Israeli friends that the undercurrent murmured in the competitive locker rooms was that the Russians and East Germanys were consuming a variety of drugs. This belief fueled the gossip mill among athletes from college age through the Olympic ranks. Since I had coached Olympic athletes previously and was currently working with the college team members, I thought that this would be an excellent opportunity to determine the precise effects of anabolic steroids on strength and performance. I could evaluate both mechanical and neuromuscular factors and determine what, if any, effects the anabolic steroids had.

Another important consideration was that all dissertation research had to be unique. It was well known in the medical scientific literature that physicians routinely prescribed anabolic steroids to hospital patients. However, the patients were frequently elderly and/or had been bed ridden for long periods of time and their muscles had begun to atrophy. However, no one knew what the effects of anabolic steroids on healthy, well-trained athletes were since that group had never been studied. I was convinced that this research topic would be both timely and unique which should be perfectly suitable for a dissertation. I discussed the idea with Professor Ricci and he agreed that the idea had merit.

The next task was to devise a scientific strategy to determine if the anabolic steroids had any effects and, if so, what were they. Since I taught weight training classes and coached Track and Field athletes, I optimistically placed a “Volunteers Wanted” sign-up sheet on the wall next to the weight room door. I was shocked to discover the next afternoon when I went to class that the page overflowed with names. There were many more volunteers than the 30 subjects that the study needed. After careful screening, the men were divided into three normal and homogeneous representative sample groups. Then each potential subject was sent to the infirmary for thorough physical exams by the physicians to ensure that they were healthy and could participate in the research proposed. After the men were cleared by the doctors, they were assigned to a group. The subjects were unaware that there was any difference between the groups. However, the infirmary placed one-third of the men in a placebo group, a second third were in the anabolic steroid group, and the remaining men were in the control group. They then sent the roster of men to me.

The control group followed the same exercise protocol as the other groups but did not receive any “pills”. Their performances on the exercises constituted the extent of their participation in the study.

Each week, the other subjects would report to the infirmary for an assessment of their continued good health and then they would be given a container with that week’s prescription. At the midpoint of the experiment, the infirmary would reverse the groups so that the subjects initially receiving the placebo would be administered the anabolic steroid and vice versa. This information was not shared with the subjects who all thought they were receiving anabolic steroids throughout the study.

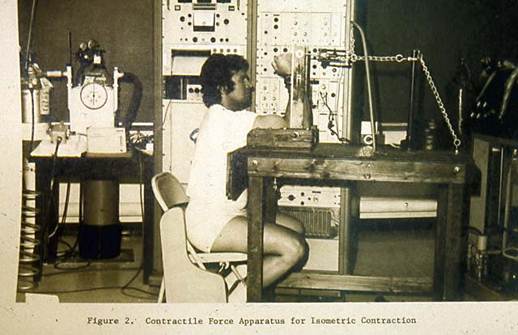

All of the subjects in the experimental groups reported weekly to the testing laboratory for specialized strength evaluations which I conducted. I measured their strength with a device which I had specifically designed for testing isometric strength. The apparatus was constructed to obtain accurate and consistent isometric strength measurements for all subjects. Isometric strength is the maximum force the muscle can produce in a fixed position. I selected as the test position, a seated subject with the upper right arm supported on a table, the elbow fixed at a right angle, and a cuff around the wrist. The subject then pulled against the wrist cuff as forcefully as possible and the strength was recorded on the computer.

Device for measuring isometric strength

Another weekly test was to measure the patella reflex. A reflex involves responses of nerves, ligaments, tendons, and muscles. However, simply put, the patella reflex is what your leg does when the doctor hits you in the knee with that little hammer. For my dissertation study, a special procedure involved placing electrodes on the right leg so that, in addition to the reflex itself, I could evaluate some of the neurological components.

The third component of the study was a prescribed weight lifting program. Every day, all the men had to following a specialized training program and record the amount of weight they lifted each day for each exercise. I collected these results every day for processing.

The experimental subjects reported to the infirmary every Monday morning for their battery of physical tests and then received their weekly dose of pills. The study progressed nicely for about three weeks and I was amazed to watch the progress of the people on the various tests. Of course, at that point, it was merely my observations but all of them seemed to be increasing in strength. I was excited about the study and convinced that it would yield fascinating results garnering worldwide interest especially among coaches and athletes.

On Monday of the fourth week, I was working with some of the subjects in my one o’clock weight training class when Dr. Ricci rushed into the weight room. His hair was disheveled and windblown, his face red, and he was gasping to catch his breath. Between gasps, he told me that we had to hurry to the infirmary because the chief physician had called for an urgent meeting with both of us.

Once we were out of ear shot of the test subjects and rushing across the campus to the infirmary, Dr. Ricci explained the urgency. There was a medical problem with one of the students. One of the weekly medical tests for that subject had revealed a potentially disastrous problem which the doctor would explain once we were privately secluded in his office. My heart sank as I envisioned not only about the terrible news that I might have to present to my subjects, who were friends, but also about all of the work already invested in this dissertation study. I would have to start from scratch with a new idea. I felt more gloomy and worried with each step we took towards the infirmary.

As I sat in the chair facing the head physical across his desk, his expression said it all. My research project was doomed and I would have to begin again. The doctor explained that prior to my study, there was no scientific literature about the effects of anabolic steroids on healthy human males. Therefore, his medical staff had included, as one of the battery of tests for each subject, a test for sperm count. Unfortunately, he explained, Subject JP’s test that morning showed a sperm count of zero. They wanted me to find JP immediately and have him come to the infirmary for a retest. Hopefully, it was merely a lab error.

I jumped up and ran from the room. Since this was long before cell phones, I had to depend on his friends to know where I might find JP. Soon, he was located and we ran as fast as possible to see the doctor. Once again, as JP and I sat across the table from the chief of the infirmary, the doctor explained the reason we were there. As he listened, JP became flushed and stared sheepishly at the doctor.

“I know the rules included sexual abstinence for the duration of study,” he stammered. “But Saturday night my friends and I were eating pizza and drinking beers at one of the local student hangouts. Two of the most beautiful girls were there, sitting on my lap, kissing me, and they insisted that I go back with them to their room. I knew that this was against the study rules but I couldn’t resist. I couldn’t believe this was happening to me and it was impossible to say ‘No’ to them. They were so beautiful and insatiable. I am so sorry. I hope I haven’t ruined your study, Gideon.”

The doctor and I looked at each other and burst into laughter. What a relief to hear this tale of fun and college behavior. With our collective fingers crossed, we hoped this would be the explanation for the zero test count. The doctor told JP that he would have to drop out of the study and report to the infirmary for follow-up tests until they were confident that he was completely healthy. Then, shifting his gaze towards me, the doctor told me to continue the study according to the protocol in place. Without a doubt, I floated rather than walked out of his office.

The data collection was completed in 16 weeks. I statistically processed the results and discovered several interesting results. One finding indicated significant improvement of force and other neuromuscular patterns due to the use of anabolic steroids. Another result indicated that the increase in strength was not due only to training or psychological factors. In other studies in the scientific literature whose test subjects consisted of weak or untrained subjects, the strength increase could be due to the mere fact that they were lifting weights for the first time rather than to any steroid use. The subjects in my study were very strong and athletic prior to the study. In other words, they were already skilled in the activities themselves and improvement in strength at their level of achievement was quite difficult to obtain merely by lifting weights.

In addition, I had included a placebo as well as the anabolic steroid to detect whether merely ingesting a pill was a contributing factor to the resulting responses. The administration of the placebos and the actual anabolic steroids were reversed at the half way point in the study. This meant that all of the subjects received both placebo and anabolic steroids but in different segments of the study. The results revealed that athletes given the placebo during the first half showed little strength gain until they were switched to the anabolic steroids in the second portion. Those subjects who began with the anabolic steroids had sharp strength gains in the first half and demonstrated little change during the second part when they were administered the placebo.

At this stage, I had to write the dissertation according to the rigidly proscribed format that everyone was required to follow. Ann was enormously helpful since her English was superior to mine. Although, at this time, I had been living in America for nearly ten years, I maintained a noticeable accent when I talked and my writing skills apparently had some kind of “accent” as well. She and I worked for many long hours until it was finally finished.

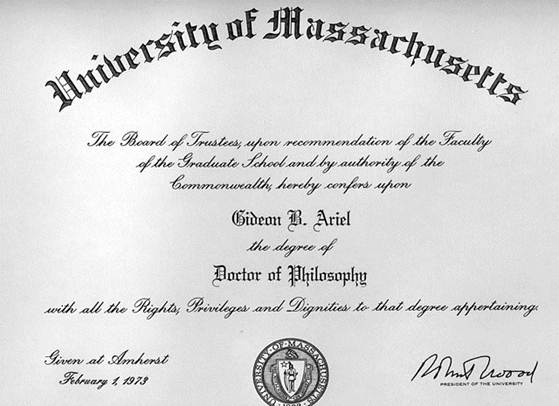

Every doctoral student had to present their research to a committee and, if successfully received, is awarded the degree. My committee was extremely pleased with my work especially because of the sophisticated statistical tools which I had used to evaluate the results. I passed with flying colors and submitted the final, printed version to the University. I was officially awarded my Ph.D. in 1972.

After completing my dissertation and receiving my Ph.D., I began to prepare the information into several articles for publication. In those days, as now, the need to “publish or perish” was a necessity especially if a student planned for a University position following graduation. At that point in my career, I was unsure of what avenue I would take, but I knew that publications would be essential on my resume.

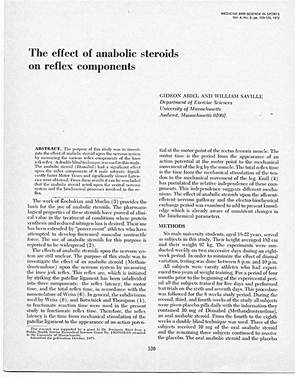

I persuaded another graduate student to help me with the articles in exchange for including his name on the publication. He readily agreed and we spent many hours writing and rewriting the material. Unfortunately, we were less precise about the details regarding which journal received which article. We mailed several different articles to a number of different publications since each article, as well as the journals themselves, targeted a variety of subject matters. As luck, and lack of attention, would have it, we sent the same article to two different journals. That would not have been so terrible except that each journal accepted the publications. Even as we rejoiced over the acceptance letters, we paid no attention to one small detail. Each letter referred to the same title and, furthermore, the letters were from different journals. We cheerfully congratulated ourselves on two articles in two journals.

Imagine the dismay and consternation we experienced the day our mail boxes contained two separate journals but with the identical article in each publications. The good news was that each of the organizations which had accepted our publications was at the top of the academic ladder. They were the Journal of Applied Physiology and Medicine and Science in Sports. The bad news was that we had committed the ultimate “sin” in academia! We had “double published”. This is a fancy term for having the same article in two different journals.

Publications in Medicine and Science in Sports and Journal of Applied Physiology

The scandal soared into the stratosphere of condemnation and blame. Eventually, when the academic dust settled, we had to write letters of apology to each organization explaining our oversight and, essentially, threw ourselves on the mercy of the editors. These letters were published in the next publication cycle in the Letter-to-Editor section complete with the editors’ chastising condemnations. We were scolded by students and professors as well. Eventually we were forgiven and have both gone on to successful careers.

During the time that I was working with my dissertation activities, I continued to take classes and was involved with the Track and Field team. The team work included daily sessions in the weight lifting room, coaching all of the Field events, and traveling with the athletes to competitions. These competitions were held indoors during the Winter session and outside during the Spring period. One day in 1971, returning to Amherst from a track meet with one of the javelin thrower, Rocco Petitto, we noticed a beautiful, quiet lake along the left side of the road. The lake, with the surrounding trees, looked tranquil and welcoming.

“Hey, let’s go look at that lake,” I said to Rocco. I had always loved nature and especially water. The lake appeared even more serene and beautiful as we drove closer. Eventually we found a placard with the name “Metacomet Lake”. Shortly thereafter was another road, Poole St., which appeared to border the lake as we turned onto it. We drove along this small road and enjoyed the beauty as it curled around one side of the lake under a canopy of tall oak, pine, and maple trees. I saw a “For Sale by Owner” sign in front of a small, reddish-colored water-front house with a phone number printed at the bottom. I copied the phone number onto a small slip of paper and put it on the car’s dashboard. The next day I called the owner who told me the asking price for the house was $15,000.

At that time, I was separated from Yael and lived in a small apartment in Northampton. The town of Northampton is about ten miles west of Amherst across the Connecticut River, and is the home of Smith College, which is one of the Sister Colleges of the Ivy League schools. My small apartment was adequate for my needs but there was no lake for my soul. “How could I get $15,000” bounced around in my head? I discussed it with Ann, who had become a close, trusted, good friend in addition to a collaborator in our shared academic classes. Her suggestion was to see what terms I could negotiate at the local bank. Neither one of us had ever borrowed money or applied for a mortgage from a bank so this was a completely new experience and a little unnerving.

Under a cloak of apprehension which we each felt but valiantly covered, we were escorted into the bank manager’s office. The banker was surprising friendly even as he asked questions from a huge list on his loan questionnaire. The questions were straightforward and I was easily able to answer them. Because I was teaching at the University, had some cash in their bank, and was beginning to generate money from biomechanical projects, he offered me a loan at a 3.0 percent rate. I called the seller, received the bank loan, and became the proud owner of that cute red house on Metacomet Lake. I was so happy to have a home of my own and on a lake as well. I knew, in addition to a home, could use it for my scientific and business activities.

My house on Metacomet Lake in Belchertown, Massachusetts

About the same time that all of the classes and dissertation data collection were proceeding, I was also traveling nearly every weekend to track meets throughout the Yankee Conference. There were competitions in Boston, Providence, New London, and Hanover. I was able to meet the coaches from the schools and share information. It was at one of the meets that my head coach, Ken O’Brien, introduced me to the coaches from Dartmouth College. The Head Coach was Ken Weinbel and his assistant was Carl Wyland. It transpired that Dartmouth College would be hosting a special Olympic Throwers Camp during the summer. Coach Weinbel asked me if I would be interested in participating as one of the coaches in this Camp. He was especially interested in the biomechanical analyses that Ken O’Brien had described. I was very excited by this opportunity and enthusiastically agreed to join the coaching staff for the Camp.

Ken Weinbel and Carl Whylan at the training camp in Dartmouth College

When the summer arrived, I had many decisions to make. First, was what to do about money. I had to find a summer job which would not conflict with the time needed to attend the Olympic Throwing Camp at Dartmouth College in Hanover, NH. Luckily, the director of the University’s Intramural program would be traveling most of the summer and needed someone to fill his position for that time. I applied and got the job with the understanding that I would have to travel to Hanover periodically.

The next task was to find someone to assist me in the data collection and processing at the Olympic camp. Although Ann would have been invaluable, she was quite busy with classes so she could only help in a limited capacity. As luck would have it, one of my student athletes, Rocco, needed to raise his grade point average with high extra credit grades during the summer class period. We made a deal that he would be my biomechanics assistant in exchange for “A” grades in three special-credit classes from me. Since Rocco was a javelin thrower for the school, he was familiar with the biomechanical work I had been performing for the team members. In addition, he was an undergraduate physics major so he brought his own knowledge to this new and developing area of biomechanics.

The Throwing Camp was three long and intense weeks. Rocco and I would drive the four hours from Amherst to Hanover, work with the throwers, and film the various performances. After a few days of filming, we would drive the four hours back to Amherst to process the data. Rocco did most of the tracing of the films and transferring the numbers onto the computer punch cards. I had to execute the biomechanical programs and interpret the resulting outputs. All of these processes were arduous and time-consuming. Rocco, Ann, and I discussed at length about finding or creating better techniques for data collection and processing.

Analyzing one of the shot-putter at the camp

Ann was involved in much of the work when we brought the work back from NH. She used my office for much of the summer since it was convenient for her classes, my intramural job, and for the biomechanical analyses we were doing for the throwing camp athletes. Summers in Amherst were relative quiet and tranquil. There were few classes available in the summer so the majority of the students and faculty left town. The campus population consisted mostly of University employees or graduate students working on projects. Our dear friend, Jim Salidas, had taken his family to a well-paying summer job which left Ann, Rocco, and I to work and study together.

Another thing I did while I was working with the Olympic athletes in Hanover, was to take some courses in the at Dartmouth computer science department. Dartmouth College had a faster, newer computer than we had at the University of Massachusetts and, in addition, there was around-the-clock access. We could send our data over a coupler to the main frame and pick up the printouts even at 2:30 in the morning. This was a marvelous advantage over the Massachusetts system so I tried to capitalize on it as much as possible.

One of the computer courses really amazed me since the two professors, Kemeny and Kurtz, had invented a new language called BASIC (Beginners’ All Purpose Symbolic Instruction Code). It was simpler, more straight forward that FORTRAN, and allowed the user to communicate with the computer via time-sharing. This meant that a user could directly connect to the computer through an acoustic coupler and “share” the computer’s processing time with other users. Since computers were larger and faster than any one individual, a computer system could host quite a number of users who simultaneously worked on the main frame. Probably, even with many simultaneous users, the computer had more capacity that went untapped. In today’s world, most people have their own computers and only connect to some type of remote access through a server or cable provider. In 1971, nothing like today’s PC or even our modern, powerful telephones existed. Bill Gates and Steve Jobs were not there yet.

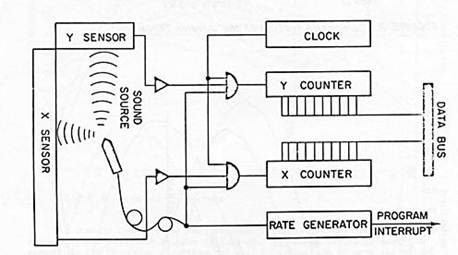

In one of the coaching sessions with the Throwers, I explained the step-by-step procedure from the throwing performance, processing all of the data collected, computer calculations, and finally explaining the results to the athlete. Later, I told Coach Weinbel that an improved tracing system would accelerate the process by many hours and should be less labor intensive. In fact, an automated “digitizer” would enable someone to more easily and quickly process the films. In addition, since I had become familiar with the ability to “time share” with the computer, I recognized that this would be a perfect marriage of technologies. I began to envision an automated tracing system linked directly with the main computer system through the telephone couplers we utilized at Dartmouth. Ken Weinbel listened to me with the same disbelieve that the kids at Hadassim had when I told them about going to the Olympics.

But, the biomechanical analysis was a fantastic solution for quantifying the sports performances despite the drawback that it was a slow tedious process. However, since I never quit, I continued to ponder a solution to this laborious bottleneck. One sunny Hanover day, Coach Weinbel suggested that I go to a particular laboratory in the Medical School to see what they used there. He had heard about some medical application using lasers. I hurried over to the Dartmouth College Medical Center and found the lab he had mentioned. I discovered that this surgical center used equipment to outline brain tumors on X-rays using a specialized pen. The patient would have four to six different X-rays taken of the tumor each from different angles or perspectives. The technician employed a type of specialized light “pen” to trace the outline of the tumor on each X-ray. Then the exact location of the tumor in the brain would be determined using a programming formula that the physicians and researchers had developed. The location had to be determined very precisely since the tumor in the patient’s brain was to be annihilated by intersecting laser beams. Any error in the exact location of the tumor would result in damaging healthy tissue.

I wondered whether I could use something like this for the film sequence of a movement. Maybe a pen could touch each joint center and sound would replace the light used to outline the tumor. The biomechanical technique needed to determine the x and y coordinates for each joint center for each frame of the film. I asked the researchers at the tumor laser lab it their system was accurate. Their response was that it was life or death for the patient so the system had better be accurate. Next I asked for the name of the manufacturer which they happily provided.

The light tracing equipment was manufactured in Connecticut in a small town not too distant from Amherst. It was not long after I saw the equipment in the Dartmouth medical department that Ann and I drove to their factory. We explained our needs and I asked whether they could build a prototype using sound. I had an idea that the bottom and side of a frame would have built-in microphones. A “pen” would create a sound that would be detected by the microphones. The pen would create a spark with a certain frequency which would propagate the instant that the glass surface was touched. The first microphone that detected the arrival of the sound would be the one located at the shortest distance from the pen in both the horizontal and vertical directions. These perpendicular microphone locations represented the x and y coordinates. The equipment would transmit the x and y values to be punched onto a paper tape. After the film processing was completed, the paper tape could be submitted manually to the computer. An acoustic coupler could also be connected so that the data could be sent directly to the computer. In this fashion, there would be direct computer connection and a backup paper punched tape. After the x and y coordinate data was saved in a computer file, the biomechanical analysis program could be executed.

Thus, by inventing the “Sonar Digitizer,” I had developed a unique device which would rapidly increase the digitizing process. Rapid identification and stored information of the body’s joint locations would greatly enhance the biomechanical quantification process. The company enthusiastically embraced the sound modification and said they would let me know as soon as it was available for us to see. On the drive back to Amherst, Ann and I could not stop talking about this fantastic device which we already were using before it actually existed.

The Sonar Digitizer

During one of our biomechanics class in the previous Spring semester with Dr. Plagenhoef, Ann had leaned over and whispered that this would be a great technique for analyzing racehorses. After class, we continued the conversation and amplified the possibilities that could be used with horses. It could be employed to predict the best horse to win a specific race, or detect an injury, or even play a part in which yearlings showed the most promise.

I told her “Let’s start a company.”

She responded, “Okay. Let’s do it.”

Now, several months later, we were driving through Connecticut towards Amherst and she reminded me about this earlier discussion. But neither of us had ever started a company, we did not know how or where or how much money was needed for such an idea. Since I had to return to Hanover the next day, we decided that the next step would be to see if anyone at the Throwing Camp had some guidance for us.

The next day, between sessions, I told Coach Ken Weinbel about our idea to form a company and asked if he had any suggestions about how to go about setting one up. He said that one of his friends worked in the Business School and he would ask him our question. The following day he had the information. The professor said that it was very inexpensive to establish a corporation in New Hampshire, a mere five hundred dollars. The fee in Massachusetts for establishing a corporation was five thousand dollars and the yearly filing fees were higher as well. I was astonished that states sharing a border could have such disparate in costs. Once again, I learned that America could be a baffling place.

In addition to finding the information I had requested, Coach Weinbel expressed an interest in being a member of our company, as an investor, if we decided to proceed with a company. I told him that I would discuss it with Ann and let him know when I came back to Camp in a few days.

Ann and I discussed the situation and decided it would be an advantage to have someone with known credit and a professor at a prestigious school as a member of our company. Therefore, Ken Weinbel invested the money we needed to incorporate in NH and provide some initial costs for running the business. For example, we needed an office and the new “sonic digitizer” which was being developed. In exchange for this cash influx, he received 50% of the company while Ann and I owned the other 50%. The company was named Computer Biomechanical Analysis, Inc. (CBA). It was the World’s first research company established for the purpose of analyzing motion regardless of whether it was human, animal, or fish. Our motto was “If it moves, we can measure it”. CBA Inc. still exists and continues to do well.

Our new partner, Ken, found a large, spacious second floor office for the company. It was located above the fire department and next door to the most delicious ice cream store in town. We had room for desks, the new digitizer, and started work on the remaining film from the Throwing Camp.

It was probably during this long summer, which was filled with work but with less pressure than during the normal school work and classes, that things began to change. Ann and I studied in the same office and worked on the biomechanical projects for the Throwers. In addition, she invited me to her apartment for steak and salad dinners so that we could continue working. Somehow, without either one of us noticing, we developed a unique and special relationship. As Ann tells it, one day she blinked her eyes wide open with the realization that she loved me! I am sure, to this day, that she was more shocked than I was. All of the time that we had been together was filled with shared ideas, interests, and dreams but without holding hands, kissing, or anything else. Our friendship had grown, strengthened, and now blossomed into love. Each of us was surprised at this discovered love but happy with the realization.

School began again in the Fall with a flood of students and faculty returning to Amherst. Life was really busy now with so many things going on at the same time. Ann and I had a full academic course loads to occupy our minds and now we had a company as well. In addition, I still had classes to teach and the team to coach while Ann continued with her research assistantship collecting data for her professor. I lived in my new house by the lake but Ann continued to live in her own apartment as we cautiously tiptoed into our newly enchanted life.

We quickly realized that for our company to succeed, we needed to let the World know that it existed and what it could do. Communication to the World about this innovative service seemed obvious, to two graduate student researchers. Obviously, information would be provided through scientific presentations and publications especially in international publications. We were so naïve at that time about the world of business.

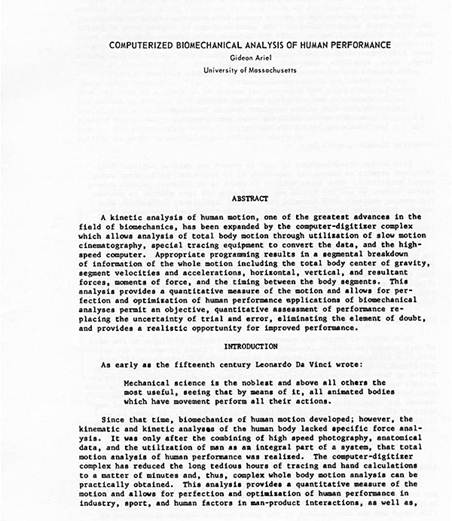

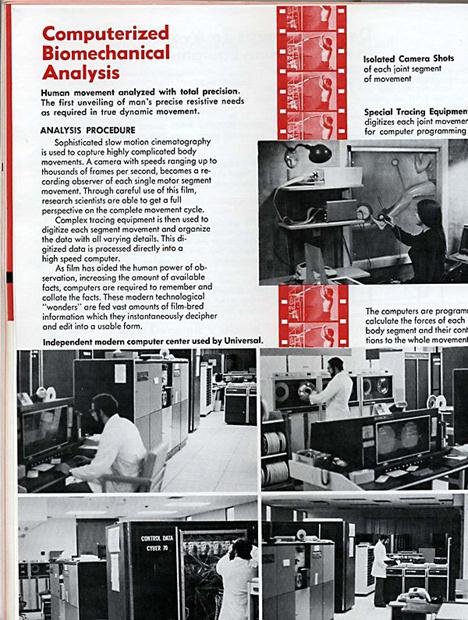

For several months, we worked on an article which described the system in a step-by-step fashion so that it could be understood by academicians and lay people. I chose the Mechanics and Sports journal in hopes that they would publish the article which included my digitizing innovation. The article was titled “Computerized Biomechanical Analysis of Human Performance” and I was overjoyed when it was accepted for publication.

A publication describing the services of C.B.A. Inc. (Published in Mechanics and Sports, 1972)

Immediately after the article’s publication, Dr. Plagenhoef called me to his office. I had been very busy during the summer and had not seen him since he had been in Maine for the summer vacation. Since I had completed his classes the previous year, I was a little surprised to receive this summons from him. I was totally unprepared for his rather aggressive tone once I was in his office.

“Why would you publish an article in Biomechanics without consulting me?” he asked.

I told him that during the summer while he was away, I had started a company dedicated to Biomechanics.

“You started a company?” he shouted.

“Yes, sir,” I answered him.

He was clearly upset and I was confused and stunned about his furious reaction. I had understood that one of the most important achievements for academicians was to publish your work and I had no idea what had provoked the angry response about starting a company. Dr. Plagenhoef continued his tirade and then I was dismissed.

I left his office with a sense that my relations with him might make things a little awkward around the department. In spite of this reaction by Dr. Plagenhoef, I was kept busy preparing publications, working on things within the company, studying, managing the weight room at the University, and working with Coach O’Brien and the Track and Field Team. As Assistant Coach, my responsibilities were to coach the Shot-Put, Hammer, Discus and Javelin events.

Our dream for CBA was that both professionals and amateur athletes would come to us for help. Our analysis of the way they ran, swung a bat, or kicked a ball would assist them to perform better or to avoid an injury. Now all we needed were paying customers. Since I had begun to attend academic conferences and present my research, this seemed like a potential source. One downside to this idea was the jealousy that academicians have when someone else is more successful than they are. The other problem is that people attending these kinds of conferences are usually seeking sponsors for their own research rather than hiring other people. Since I continued to travel with the Track and Field athletes to competitions during the Indoor season, we considered the possibility that there might be people who want our services among that population.

Ken, Ann and I decided that CBA needed a brochure to advertise our services. We would be able to hand them to prospective companies or mail them if we needed to send something that way. Our new endeavor was born long before the era of e-mail, web sites, or even fax machines. We actually had a prototype fax machine, but it was connected to our landline phone system which was all that was available at that time. In addition, the machine needed about 2 hours to send one short letter because the technology was so slow. Eventually we designed a brochure with a creative design on the front and slots inside which allowed us to insert letters or publications.

Our first CBA Inc. brochure

Ann and I discussed the idea of building a biomechanical laboratory in my new lake house. Although CBA had a wonderful office in Hanover, it was still a long drive back and forth to Amherst. During the summer months, our schedules had been less hectic. Now with all of us working full time, Ken, Ann, and I felt the need to reevaluate the situation. I invited Ken to my new home and convinced him that with the time sharing connections, we could eliminate the expenses in the Hanover office and move the headquarters to Belchertown. He agreed, since it saved both time and money.

In no time, the laboratory was working perfectly in my lake house. We were able to project the film onto the newly invented digitizer which was placed in the division between the living room and the kitchen. The digitizer was connected to a teletype, for recording the coordinates on paper tape, and directly to the main frame computer through the acoustic coupler. This arrangement allowed the data to be transmitted directly to the computer which saved hours of work which had previously been needed for punching cards. In addition, the paper tape provided backup in case anything happened during the direct transmission.

Ann digitizing on our home Biomechanical system

It was fortunate that we had developed a backup system. As every scientist and engineer knows, things can go wrong and soon after we moved the laboratory to Belchertown, it happened to us. One day, during a digitizing session, the computer connection began transmitting scrambled data. This was a disaster since we needed flawless interaction with the computer. It was dreadful to discover that the data transmission was garbled, but what could have caused things to go wrong? What could be the source of the noisy interaction? Each connection among the equipment was checked. We restarted the projector and the digitizer but nothing corrected the noise problem. Finally, I lifted the phone from the acoustic coupler and listened. There was a strange buzzing noise which I had never heard before. I shouted into the phone to see what would happen. After about two minutes of shouting, someone answered me.

“Who are you,” I enquired?

“Who are you,” a man answered.

After a few minutes of discussion, we discovered that we were neighbors across the street from each other. This was during a bygone era when people had to share phone lines in what were known as “party lines”. There could be two, three, or more homes connected to the same phone line and you had to share it with each other. What had transpired was that every time our neighbor had tried to use his phone, he heard the screeching sound the coupler made. Since he had no idea what the noise was and the noise seemed to always be there, he was never able to use his phone. Finally, in desperation, he put his electric razor next to the phone and just let it run. Here, then, were two families baffled by crazy phone noises.

How were we going to convince the phone company to give each of us a single family phone line since the homes around the lake were more rural and remote than in a big city? At that time, there was only one phone company and this monopoly was notoriously stubborn and insensitive when dealing with little, powerless people. I guess the uniqueness of our situation must have played into the decision, but eventually we were given a direct, unshared line to our kitchen laboratory.

Shortly after the phone situation, we expanded our staff. During one of my trips to Dartmouth, I was chatting with Ken Weinbel’s assistant coach, Carl Wyland. Carl was a good shot-putter who had thrown the shot more than 60 feet. On this particular day, he showed me his female dog and her six puppies. The mother was a pedigreed Siberian husky but the father was the Newfoundland milkman who had sneaked into the backyard. Carl gave me one of the furry little guys and I named him “Ringo” after one of the Beatles in the British musical group. Ringo became CBA’s first employee.

Our newest staff members, Ringo and Melich

Our second employee arrived shortly thereafter. On a chilly September evening after a late dinner, we returned to the office to work a few more hours. Somehow, crickets always found a way into our office and then had to be relocated outside by Ann since she would not allow them to be killed. That evening, when she was providing a new home for a wayward cricket, there was a “meow” and, when she looked down, a large cat was rubbing against her leg. The cat followed her into the house and enjoyed a hearty meal and drank quite a lot of water. Apparently he must have wandered away from his home and found us. This was at the beginning of the school year when Amherst was inundated with new students, returning graduate students, and faculty members returning home. We tried for several days to locate his owners but to no avail. So now we had another new staff member. We named him Melich which is “king” in Hebrew. The first few minutes when Ringo and Melich were formally introduced to each other, there was a little tension. However, I explained that now they were our family members and employees and, therefore, they had to be friends. I guess they understood my accent because they were happily together for the rest of their lives.

Now that school was back in session for the normal school year, I had to drive from Belchertown to my office at the University in Amherst every day. Regular classes, dissertation work, and coach responsibilities were back in the forefront of my work day.

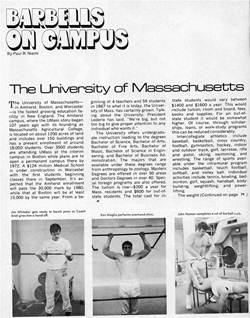

My Track and Field athletes trained four hours each day, seven days a week. This was the commitment I required if they wanted to be on the team. Without this devotion to their personal fitness, they would be wasting my time and theirs. The strength and fitness program in the Weight Room, thus, became well known on campus and new athletes continued to join the training sessions. Then, unexpectedly, I received a call from one of the editors of the magazine, Strength and Health. Bob Hoffman was the founder of the magazine as well as of the York Barbell company. Mr. Hoffman was instrumental in bring Arnold Schwarzenegger to the USA from Austria. Bob Hoffman’s picture, taken during his body building days, had graced my wall when I just a young boy in Hadassim.

It was a pleasant surprise to learn that the editor of this magazine wanted to do a story on the training methods I used. I had no illusion that some of the professors, including Dr. Plagenhoef, would be annoyed with me when they learned about this development. I continued to experience a nascent, but growing, impression that these kinds of opportunities were going to have a negative effect on me in the future. Despite the encouragement to publish and achieve success, independent publications, private companies, publicity, and other types of success were not supposed to happen to graduate students. Maybe, they were not supposed to happen to me.

Publication in Strength and Health – (I am on the right wearing shorts)

During this same time frame, Ann and I continued to pursue our doctoral programs in the Exercise Science department. Ann concentrated on Motor Integration which belonged to the field of Neurosciences and I concentrated on the field of Biomechanics.

My two publications also advanced my reputation in the field and I began presenting various studies at national and international meetings around the World. One of my presentations was given to the American College of Sports Medicine in Baltimore. The title of my presentation was the same as my publication in the Mechanics and Sports Journal, “Computerized Biomechanical Analysis of Human Performance”. For my presentation, I utilized the typical format employed at that time. This meant that I had to project 35mm slides onto a screen and discuss what each slide represented. The ability to connect your own PC and use PowerPoint and animated graphics were far into the future. However, at this conference, I presented my computer programs and demonstrated how it was now possible to biomechanical analyze human performance.

After my presentation, many of the scientists and attendees chatted with me about the subject matter. One fellow was Ed Burke, the American Hammer Throwing record holder, and he asked me whether my system could analyze people performing an exercise skill such as the bench press. I assured him that it was quite possible to measure such a performance. We had a lengthy discussion over dinner about his hammer throwing, my discus background, the recent article in Strength and Health, and the exercise machine company where he worked.

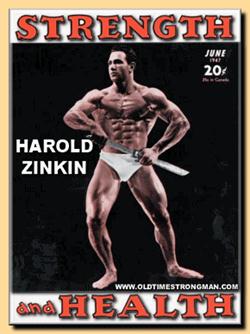

Ed told me about his boss, Harold Zinkin, who lived in Fresno, California and who build a line of exercise machines which were marketed under the brand name of Universal Gyms. At one point in his youth, Harold Zinkin had been Mr. California. One of Harold’s best friends was Jack LaLane, who was possibly the most famous fitness guru in the 50’s and later. For years during their youth, these two friends had worked out on the sunny beaches of Venice, California. Venice was called “Muscle Beach” because of the large number of devoted weight lifters who trained, and flexed their muscle for all of the admiring public to see. There were also many competitive challenges among these weight lifters and body builders. However, there was one stunts that none had successfully accomplished despite repeated efforts. The stunt, nicknamed “”pyramid”, was to have the first person arch his back into a backbend or wrestler’s bridge. The second man could stand upright on the stomach of the first person. Then in stacked formation, the third and fourth men stood on each other’s shoulders balanced on the shoulders of the second man. In other words, three men stood on each other shoulders while the man at the bottom of the “pyramid” supported them in a back arch position. Success was only achieved if they were able to hold the configuration for three seconds. Everyone struggle to achieve this feat but only Harold Zinkin, Jack LaLane, and their two friends, “Moe” DeForest and Gene Miller, were ever able to successfully create and hold this human structure. I was pleased and thankful that Harold provided an opportunity to meet Jack LaLane and have him train on my exercise machine. They were both fascinating men who loved life and were willing to share their joy with others.

Harold Zinkin Harold at the bottom, LaLane is the third one

At some point during the dinner, Ed asked me if I could fly to Fresno to talk with Harold. I readily agreed and we discussed some potential dates. After I returned to Amherst, Ed and I communicated and found a date that did not conflict with my very full schedule. Although I was stretched in many directions at that time, Universal Gyms seemed like a natural potential customer for CBA and so I flew to California.

Ed introduced us in Harold’s office. What I noticed immediately about Harold was his incredibly muscular build despite his age. I was in my 30’s and trained every day but Harold was twenty years older and was still a powerful, muscular man. He came around his desk and shook my hand. His grip was firm and his smile was infectious. He gave me a little tour of the amazing pictures on his wall which included photos of famous people he knew. Prominently placed was the infamous “pyramid” of him, Jack LaLane and their friends. There were also some marvelous oil paintings that his wife, Betty, had painted.

When we sat down, he said, “I heard that in one of your presentations, you called dumbbells and exercise machines dumb. You said there is a need to develop an intelligent machine. Okay. How would you do it?”

I explained to him that the human body is made of levers and muscles in configurations so that, when you lift a weight, there is a mismatch between the resistance and the position of the limb at that point.

“And?” he asked.

“A better design would be to vary the resistance based on the limb angles and levers.” I thought for a moment. “What we need is a mechanism on the equipment that can vary the resistance. In other words, we need to devise a machine or mechanism that can compensate for the changing lever systems of the human.” I explained.

“How would you do that?” he asked.

I told that most exercise machines are designed merely from personal observations and ideas. They lack scientific data relating to each individual athlete or his specific performance. That is to say, a device might purport to exercise a specific muscle or group of muscles but, without proper testing, it is impossible to know whether or not the claims were correct. Whether or not someone exercises efficiently cannot be determined merely by visual observations. Leonardo de Vinci looked at birds. But none of his brilliant designs, impressive though they were, allowed men to fly. It is possible to have a good concept but the idea needs to be tested quantitatively in order to create a machine that can actually produce the desired results.

“We need to build,” I explained, “an exercise machine that takes into consideration the natural changes that occur in the human lever system while performing any movements that necessitate different levels of muscular involvement. In traditional weight training equipment much of the effort is wasted because the muscle-leverage system changes throughout the movement.

“Pick up this twenty pound weight and hold it at your side. Then lift it slowly upward keeping your elbow locked until your arm is straight out at shoulder level. You can feel how much more your muscle has to work as you lift the weight. Now try the same movement with this 100 pound weight. Most people would not be able to lift the100 pounds very far. What this means is that all weight lifting with barbells and dumbbells is restricted to the amount you can lift at your weakest point. Imagine performing that lifting exercise holding a heavier weight and, as you raised the weight, a magic genie would remove some of the weight as the exercise became more and more difficult. In other words, the weight would ‘vary’ as you raised your arm. You could start with a heavier weight and as the movement progressed, the amount of the weight would change. We need to find a mechanical solution to provide this ‘magic genie’ in my example.” I concluded.

He nodded as he replaced the weights in the rack at the back of his office. Then he sat back down.

I continued, “In order to develop maximum conditioning effectiveness, we need to accurately vary the resistance. The variations in resistance should occur only when there are biomechanical advantages or disadvantages which decrease or increase the required muscular efforts. By varying the resistance accurately, it is possible to maintain the same degree of muscular involvement or effort throughout the entire range of movement.”

“Give me an example of how you would do that.” Harold replied.

“Every exercise will be different.” I replied. “For example, when you execute a biceps curl, your arm is strong at the beginning, weak when the elbow reaches the 90 degree angle, and strong again when your hand reaches the shoulder area. However, there is an entirely different force profile for the leg extension and the bench press would be unlike the first two I mentioned. The only way to accurately determine what the force profile should be for each exercise is to perform a biomechanical analysis of them.” I continued.

Harold said, “Gideon, do you think that you could redesign our existing equipment using your biomechanical evaluation? If you think that it is possible, I want you to proceed immediately and send me the bill. By the way, I want the results as soon as possible.” He smiled broadly at the last comment.

I told him that I would need to have some of the machines he currently manufactured in order to begin data collection on them. Since I had a large basement in my house, he could ship the machines to me and I could make the measurements there.

I realized how serious Harold was about wanting the information quickly because less than a week later, a large truck arrived at my house with some Universal gym equipment. The equipment was a large, square with 16 different exercises that could be performed on it. In addition to the equipment, Harold arranged for one of his mechanical engineers, Ken, to spend time with us to collect and process the data. Ann, Ken, and I filmed the equipment and traced the movements using our new sonic digitizer. Then Ken calculated some of the mechanical changes based on the quantified results that would have to be made in order to have the resistance vary for each different exercise.

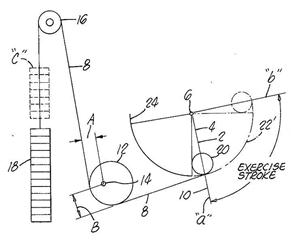

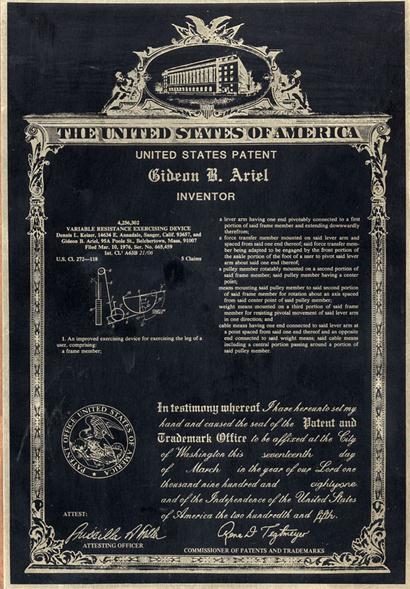

Eventually, our calculations and biomechanical analyses led us to devise a cam and lever system. The cam system we developed was the first one ever used for modern exercise equipment. We were able to use a cam directly for most of the single joint movements, such as the biceps curl, and then we had to develop a modified system for the multijoint exercises.

For example, the biceps curl station on the equipment was modified to utilize a carefully calculated cam which provided resistance throughout the entire movement. The biceps curl station cable went around the specially designed cam and attached to the weight stack. Thus, when the person pulled on the cable, the cam provided changes to the moment arm on the cable. Thus, the weight “varied” appropriately as the individual flexed the arm.

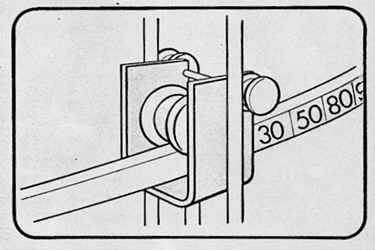

Weight Stack controlled by a CAM to dynamically vary the resistance (Patent by Gideon Ariel)

For the multijoint exercises, such as the bench press, we had to devise a modified cam to accomplish the task. This devise utilized a “sleeve” which rolled on the bar. The bar was attached to a section of the frame opposite to the weight stack with the handles at the exercise station. A specially designed “sleeve” was connected to the weight stack which rolled as the bar moved up and down. When the person pushed up on the handles, the bar moved up. The “sleeve” rolled on the bar as it was pushed up. As the bar moved up, the selected weight moved with it so that the moment arm changed throughout the range of the movement. In other words, the rolling or sliding “sleeve” on the bar altered the amount of resistance the person had to lift. This change in the location of the weight on the bar relative to the person exercising provided the variable resistance.

Mechanism to vary the resistance on the Universal Machines Bars

Ken took the calculations with him and flew to Fresno. Shortly thereafter, I flew to California to check the prototypes that Harold had built based on our calculations. For several months, we performed additional biomechanical analyses and finally perfected the variable resistance mechanisms for each of the 16 stations.

Harold appointed me as the Head of Research for Universal Gym. We named the new exercise machine line as the Dynamic Variable Resistance mechanism, or DVR. All the Universal Machines incorporated these mechanisms of cams or levers that adjusted the resistance to the movement of the athlete or the person who trained on the machine. This new concept machine was an immediate success among schools and athletic teams. The introduction and growth in sales of the DVR helped the company expand and their revenues grew exponentially.

The Universal Gym Project

The new brochure which Universal created introduced the variable resistance concept as well as me personally. I was proud that I was so prominently included in their advertising brochure. For our company, this was a fantastic development since we received publicity as well as payment for the scientific analyses.

The Dynamic Variable Resistance Mechanism brochure

Our relationship progressed nicely with Universal. Both Ann and Ken Weinbel were pleased about the success we had with this project and with the continuing involvement with Universal. It was also helpful that I was asked to attend many of the fitness trade shows to describe the DVR concept. Our company, CBA, profited from this publicity. The more well-known I was, the better for CBA.

In one of my meeting in Fresno, Harold said, “Gideon, we would like to pay you royalties for each machine we sell. How much do you think would be fair?”

I told him that I had no experience with this situation. Since he had been fair with us in all of the projects to date, I told him that I trusted him to decide on a fair amount.

“How about $350 per machine?” he asked.

“This sounds great,” I replied. After that meeting, we received royalties on each machine that Universal sold. At one point, they sold more than five thousand machines per year so the effort which we had previously expended was nicely compensated.

Shortly thereafter, Ann accompanied me to Fresno to work on the current project. Harold asked for a meeting and his first question was “Gideon, what do you do with the royalty checks we send you?”

I shrugged and said that I put them into the bank. Harold asked whether I kept a bank book with deposits and withdrawals. I told him that normally I had a general idea in my head as to how much money was in the bank account. Nodding his head, Harold called for his secretary to come into his office.

“How many checks have we sent to Gideon and how many has he cashed?” he asked her.

“We have sent twenty checks and he has cashed fourteen of them,” was her answer.

At this point, Harold turned to Ann and inquired whether he could hire her, with Gideon’s agreement, to act as his accountant regarding the deposits of the checks from Universal and maintenance of his bank account. I laughed and readily agreed that Ann would be perfect for this task. Ann agreed as well and was shocked when Harold said he would pay her fifty dollars a month to perform this task. At that time, fifty dollars went much farther than it does in today’s world.

Harold also told me that I should apply for a patent for the DVR since I had invented the system. He said that Universal would do all of the paperwork and legal processes at their expense. However, the patent had to be issued to a person not a company. The patent was issued and, for the first time, a cam or a mechanism to vary the resistance based on anatomical and biomechanical conditions was incorporated into Exercise Machines. Today, any gym with a cam-based machine is a copy or an application of my idea and this patent. This method of varying the resistance revolutionized the resistive training methods for many exercise machine companies and many publications resulted from it.

First Patent for cam-based exercise machines

As luck and hard work would have it, we now had an office with equipment, a computer connection, and some money from Universal. We had real biomechanical power and hoped that soon there would be additional money-making projects. One day, a man from the Spalding Corporation called. He introduced himself on the phone as Egon Romacker and said that he was the Director of Research at Spalding Sporting Goods in Chicopee, Massachusetts. He had read my article in Mechanics and Sports and wondered if we could meet to discuss some ideas that he had. We arranged a time and date for lunch at the Yankee Peddler, a restaurant in Holyoke. I dared not invite him to my laboratory in our kitchen. Ann and I dressed nicely, which meant we changed out of the blue jeans and T-shirts which were our normal attire, and drove the 20 miles for the lunch meeting.

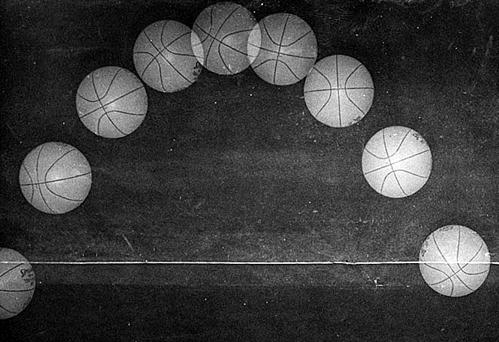

At the restaurant and, following our round-robin of introductions, Mr. Romacker told us how impressed he was with our technique of analyzing athletes. His questions involved whether we could also trace and analyze other objects. I asked him what objects and he answered, “The flight of a basketball.”

“Of course,” I replied without hesitation, although I had no idea whether we could do it or not. However, to secure our first real project, I confidently believed we could analyze anything. Egon explained that Spalding was the leading basketball manufacturer in the world. However, they had been attacked by some competitors who claimed that Spalding basketballs wobbled in the air. That is to say, they had been accused of producing basketballs similar to the crazy distorted ones that the comedic basketball team, the Harlem Globetrotters, used. One of the jokes the Globetrotters included in one of their less-than-serious routines was to give their opponent a ball that wobbled and swayed all over the court following unpredictable and irregular paths. This accusation against Spalding’s basketball production could have serious repercussions in their market and, thus, their profitability. The question Egon asked us was whether we could ascertain the actual flight of their basketballs and, if there was a problem, could we provide a solution to solve it. In other words, did their basketballs follow a parabolic flight, which gravity dictated, or did they wobbled during flight.

Obviously, the ball would have to be perfectly balanced as it revolved around its center of mass. If one part of the ball was heavier or lighter than the other parts, it would wobble. Throughout the lunch, we discussed the various factors associated with ball flight and briefly created a proposed testing protocol. We would have to determine whether the center of mass was located at the center of the ball. Egon agreed with my assessment but told me that they had measured it numerous times with engineering firms and spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to show that the center of mass was exactly in the center of the ball.

“Well,” I suggested to him, “we should set up the test area in an area in a gym where we can launch the ball from a machine. With a machine to launch the balls, there would be no human interactions which might contaminate the movements. The test results would be completely objective. Also it would be a dynamic test rather than a static test which is what most engineering firms perform. We are the only company which can evaluate dynamic, as well as, static conditions. We will bring our high speed cameras, film the flight of the ball, and calculate both the center of gravity and the center of the ball. These films and calculations will determine whether the balls follow a parabolic path or not.”

Mr. Romaker asked me how much the project would cost. I told him that I would let him know the next day. Spalding could provide the ball throwing machine and would find a local gymnasium for testing that would be conveniently close for both of our organizations. He told us to call him with a proposal as soon as we were ready.

When we drove back to Amherst, Ann and I were very excited about having our first project. I called Ken Weinbel and shouted “Ken, we have a project!”

Ken was excited, too. He asked “How much are you going to charge for this project?”

I asked him how much money he had spent so far on the company, total. He told me that it was about $12,000 including the corporation registration with the State of New Hampshire, the digitizer, purchasing the two projectors and the two Kodak Special 64 frames per second spring loaded cameras. I said that I would call him the next day after we spoke with Spalding.